Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431)

("Concerning the fact of the Maid and the faith due to her")[1]

Saint Joan of Arc called herself, Jeanne la Pucelle,[2] meaning "Joan the Maid." Her followers called her, simply, La Pucelle. Her antagonists spitefully called her "the one who calls herself the Maid" or "Joan who calls herself the Maid."[3]

These pages present a Catholic view of Saint Joan that is consistent with the historical record. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan of Arc, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of Joan, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her life and legacy. The verity of Joan's visions (which we will call her "Voices") is assumed here, which enables important typological and scriptural connections to Joan's life and acts. Presented here, as well, is the theory that Joan's mission was not to save France so much as to save Roman Catholicism.

This article assumes everything that Saint Joan did, experienced, and testified, according to the historical record, was real, not just to her, but objectively real.

Please note that the discussion of Saint Joan here is analysis not narrative. Although the narrative is presented, the approach here is thematic not chronological. To review a straight chronology of her life, please see the Joan of Arc Timeline or find a good narrative treatment of her from the Joan of Arc bibliography.

Background to the story of Saint Joan of Arc

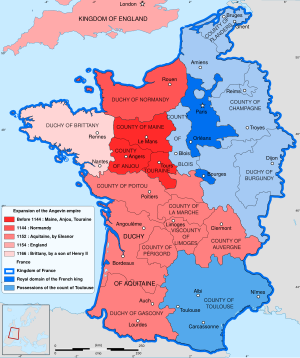

Joan was likely born in January of 1412 in a village in eastern France that lay on the margin of warring French factions and the quasi-independent Duchy of Lorraine. She was about eight years old when in 1420 the French King Charles VI "the Mad", in the Treaty of Troyes, granted to Henry V of England succession to the French crown through marriage to Charles' daughter. Henry had ascended to the English crown in 1413, proclaiming himself also, as did his predecessors, King of France. He reasserted English claims on France, including former English possessions in Normandy and western France, which the French, either disunited[4] and so unable to address it cohesively, or simply did not take seriously.[5]

In 1415, Henry invaded Normandy, reviving the ongoing but episodic French succession conflict we now call the "Hundred Years War". At the Battle of Agincourt, Henry destroyed French forces that consisted mostly of loyalists to the House of Orléans, while its French rival, the House of Burgundy, sat it out, perhaps even by agreement with the English.[6] Animosity continued between the French factions, further weakening the French King, Charles VI, who suffered attacks of severe mental illness. In 1419, followers of the Dauphin murdered the Duke of Burgundy, which opened the opportunity for Henry V to push for a settlement with Charles VI in the Treaty of Troyes. The Queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria, supported the deal which, through marriage to him of her daughter, yielded succession to Henry as King of France, thus cutting off her son, the Dauphin. With the Duke of Orleans in captivity in England, the Dauphin sidelined for the murder of the Duke of Burgundy, the Treaty was largely negotiated by the Burgundians, including a Bishop[7] who would later persecute Saint Joan. It was formally ratified by the Estates-General at Paris, where Henry V, under Burgundian endorsement and protection, arrived to sign it.

There's all kinds of messiness here, what with Charles VI bouncing between delusions and paranoias, his wife running the Court during his episodes, and rumored to have had an affair with the King's brother, who in 1407 was murdered by the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless who was himself murdered in 1419, perhaps on orders her son the Dauphin, who, the Burgundians claimed, was actually son of the Duke of Orleans[8] and not of the King. The rumors of this illegitimacy served the Burgundian cause and alliance with the English, but the French loyalists, known as the Armagnacs, supported the Dauphin regardless. One the death of Charles VI, the Dauphin assumed the throne of France as Charles VII, while Henry V assumed it Henry II.

The war escalated from there, with each side took some victories, although the English secured their hold on northern France and in 1423 and 1424 inflicted two overwhelming defeats of the French and their Scottish partners.[9] Meanwhile, the English prompted the Burgundians to wage slash and burn tactics on areas of French loyalists, including Joan's village of Domrémey, which was subjected to occasional raids and ransoms.

Around this time, at the age of thirteen Joan began to experience voices and visions. Her "Voices" instructed her to lead a Christian life and, later on, to "go to France" to save save France and crown its King, Charles VII, whom Joan knew as the Dauphin. In late 1428, Joan's Voices became urgent, telling her she must relieve the city of Orleans from an English siege that had begun that October.

So what did Joan actually do?

To save France, Joan needed to crown the Dauphin legitimate King of France; to crown the King, she needed to relieve the city of Orléans from an English siege and then clear the way to Reims for his coronation; to take the city of Orléans, she needed to lead the French army; to lead the army, she needed the support of the Dauphin and his court; to get the support of the Dauphin she needed to convince him of her divine mission; to convince him of her divine mission she had to do meet with him; to meet with him, she had to generate enthusiasm and curiosity as to who she might be; to convince people she was the fulfillment of a legend of a girl who would save France, she had to be thoroughly convinced of it herself; to convince the Dauphin's court, she had to demonstrate Catholic orthodoxy to ecclesiastical interrogators; to earn the loyalty and enthusiasm of her fellow military commanders, she had to exercise tactical brilliance and remarkable bravery.

To those ends, several things stand out:

- She believed and obeyed her Voices;

- So convinced, she wouldn't take no for an answer;

- She accurately prophesized events and outcomes;

- She generated tremendous enthusiasm from the people;

- She breathed confidence into the French army, which had been browbeaten and self-defeated until she inspired them with her leadership and example and disciplined them through the Confessional and the Mass;

- She exercised decisive military and political leadership, knowing when and where to attack at key moments and the crucial next steps towards formal coronation of the Charles as King of France;

- She scared the crap out of the English;[10]

To become a Saint, she had to suffer betrayal and martyrdom after a uniquely well-documented show trial at the hands of the English and Burgundians, the "Trial of Condemnation"; to preserve the memory of that Trial, her mother and others faithful to and believing of her had to convince the French King and the Pope to reassess her prior conviction in a similarly uniquely well-documented investigation called the "Trial of Rehabilitation."

All this, I argue, she did to save Catholicism.

Saint Joan of Arc saved France, and doing so saved Catholicism itself, which I propose was her divine mission all along. She was canonized by the Catholic Church on May 16, 1920.

Notes on page readability and navigation:

- Select expand menu on the top left to view and navigate between page sections (chapters).

- Use the "Appearance" menu to the right to adjust text size and page content width.

- This page employs extensive footnotes for reference and further discussion of the in-line text.

- for ease of reading references, hover over (or touch) the footnote number and the notes will appear.

- if you click on the footnote number, it will take you to the References section at the bottom of the page.

- on mobile phones, touch and hold will show the footnote, whereas on Windows 11 tablets it will take you to the footnote; recommended is to your mouse hover either with a mouse or mousepad, or using the Windows virtual mousepad.

- click on images to enter full screen, slideshow view, which enables scrolling through all images

- hit escape or back to return to the text

Copyright © Michael L. Bromley, 2024-2025. All rights reserved. All content provided on this website, including but not limited to text, graphics, images, and other material is for informational purposes only. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited.

This website is built on MediaWiki, the same platform as Wikipedia. This site is unrelated to Wikipedia, although it does graphics hosted by Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons and which are in the Public Domain.

Related pages:

- Joan of Arc Timeline

- Joan of Arc bibliography

- Kings of France and England

- Popes and antipopes

- Saint Joan of Arc Glossary for names, places & terms, as well as a flow chart of the lineage of French Kings (which can otherwise be confusing)

- The Life of Joan of Arc by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel (with Joan of Arc series from National Gallery of Art)

Here for Saint Joan of Arc category list of related pages

Joan the Maid (Jeanne la Pucelle)

At her "Trial of Condemnation[11] held under English authority," Joan testified as to her name, explaining,[12]

In my own country they call me Jeannette; since I came into France I have been called Jeanne. Of my surname I know nothing.

Jeanne, or Jehanne, is feminine for John, which means "God favors," and which is echoed by the name given her in the sole literary work composed during her time, the Pucelle de Dieu ("Maid of God").[13] Joan may have been called Petit-Jean, by her family, after her uncle Jean. More importantly, her "voices" -- God's messengers -- called her "Daughter of God":[14]

Before the raising of the Siege of Orleans and every day since, when they speak to me, they call me often, ‘Jeanne the Maid, Daughter of God.’[15]

It was not until after her martyrdom that she was called "Joan of Orleans" or "the Maid of Orléans" in reference to her miraculous intervention in the Hundred Years War, the turning point of which was the relief of the city of Orléans from an English siege conducted under Joan's improbable and brilliant military command.

While we know her as Joan of Arc, neither she nor her contemporaries used the surname, "of Arc" (d'Arc), which was a 19th century invention based on her father's surname, Darc, which appeared during posthumous investigations called the Trial of Rehabilitation[16] starting in 1452, nine years after her death.[17] The name d'Arc arose as one of several varieties of her father's family name, Darc, Dars, Dai, Day, Darx, Dart, or d'Arc.[18] A possibility is that her father's family had originated in the village Arc-en-Barrois, which would have made for the surname "Arc" or "d'Arc".[19] The name Arc is derived from the French for "arrow," which would be fitting for Joan's presence and effect upon her times, and, besides, d'Arc is the coolest sounding of the batch, so perhaps that's why it stuck.

Joan testified that girls in her village did not use their paternal surname and instead used that of the mother. Hers was Romée, which makes for an interesting connection in that the name derives from "Rome," indicating a pilgrimage to Rome at some point by an ancestor.[20] Along with a similarly possible etymological origin to her village name, Domrémy, the connection to Rome becomes interesting to us insofar as at her trial by the English Joan stood resoundingly for the Roman Pope over the schismatic antipope who had before been supported by her compatriots in France, as well as to request an audience before, like Saint Paul appealing to Caesar, the Pope in Rome.[21]

Joan, Handmaid of the Lord

It is often observed that Joan used Pucelle, for "maid," or "maiden," to emphasize her virginity.[22] In common usage today, the masculine puceau directly means a man who has not had sex. However, the feminine pucelle then and now means either "young girl" or "virgin," but not necessarily both, although the association may be made.[23]

But for Joan, "maid" or "handmaid," as it could also be translated, makes a clear reference to the greatest "handmaid" of them all, Our Lady, the Mother of God. Joan was devoted to Mary,[24] and had inscribed her name atop her battle standard along with that of the Lord: "Jhesus † Maria".[25]

Joan, like anyone in her day, would have made that connection of the word pucelle to the words of Mary herself:

Mary said, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word.”[26]

They would have known the passage from the Latin Vulgate[27] with the term, ancilla, which is a female servant or slave and not necessarily a virgin:[28]

dixit autem Maria ecce ancilla Domini

The Vulgate New Testament was translated from Greek, so we can go to the original Greek word in Luke 1:38, δούλη (doulē), which means "slave woman" or "female servant," both of which become in English, the traditional "handmaiden", the meaning of which is directly "female servant."[29] In her home parish, Joan would have heard the Gospel in Latin, but if her priest ever preached the passage in a homily -- a certainty -- Joan would have heard not just the direct translation into French,

Marie dit: Je suis la servante du Seigneur

but also the reference to Mary as,

la Pucelle Maria

as "Virgin Mary" as was used commonly at the time.[30] So "pucelle" and "servant" are distinct but both accurate references to Mary. Yet, if we think of Pucelle solely as a virgin, we are missing the larger significance in the context of Luke 1:38, of Mary's fiat,

May it be done to me according to your word.

La Pucelle is a virgin -- and Joan was -- but more importantly she is God's loyal servant who follows the instructions of the Archangel. For Mary it was the Archangel Gabriel; for Joan it was the Archangel Michael. For both, it was the Word of God.

Crazy, Saint or witch?

Joan's biographers like to present Joan with a letter she composed to the King of England,[31] the child-king Henry VI, the day she was given authority over the French army.[32] It's a marvelous, crazy letter, almost arrogant at first glance. A second look, though, and the letter yields instead Joan's simplicity and directness. Indeed, she is hardly arrogant: just bluntly honest:

Jhesus † Maria King of England; and you, Duke of Bedford, who call yourself Regent of the Kingdom of France; you, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk[33]; John, Lord Talbot; and you, Thomas, Lord Scales, who call yourselves Lieutenants to the said Duke of Bedford: give satisfaction to the King of Heaven: give up to the Maid,[34] who is sent hither by God, the King of Heaven, the keys of all the good towns in France which you have taken and broken into. She is come here by the order of God to reclaim the Blood Royal. She is quite ready to make peace, if you are willing to give her satisfaction, by giving and paying back to France what you have taken.

It's a useful letter for the biographer, as it tells her story perfectly. But left unexplained or unattributed to anything but "voices", as they tend rather agnostically to leave it, it makes no sense: okay, so this illiterate girl from a little village hears "voices" that tell her she will save France and crown its legitimate King. She insists on an introduction to that prince, gets the interview, somehow picking him out of a crowd, undergoes three weeks of questions by all the king's finest minds, and passing the test is given a horse, lance, and suit of armor -- and essential command of the French army, whereupon she writes a letter to the King of England demanding he surrender all his possessions in and claims upon France -- while displaying knowledge of the English political and military hierarchy.

Okay...got it.

Thank you, historians, but let's try it this way instead:

God sends Saint Michael the Archangel and Saints Margaret and Catherine to visit with a worthy young girl in a small town in eastern France. Her country is both at war and civil war. The Church is in a state of disruption, with two ongoing antipope claimants, proto-protestant rumblings, and the "conciliarism" movement against papal authority gaining strength as a result of the various papal schisms. Over three years, the Archangel and the Saints prepare the young girl spiritually for her mission, guiding her to maintain a state of Grace. In 1428, as the city of Orléans is subjected to a siege by English forces, they now tell her what she will do: save the city and crown the king in Reims, a city surrounded by the enemy. Following her divine voices, she gains an audience with the French prince, convinces him of her divine mission and is made a leader of the French army. Then, invoking God's instructions, she sends a letter to the King of England and his commanders, detailing their organizational structure and demanding surrender of his French holdings. The English refuse, so, guided by providence, she leads the French army to an improbable victory which she duplicates in a series of battles that clear the way for the French Prince to triumphantly arrive at Reims, the traditional city of coronations, where he is crowned King of France, Charles VII.

Now we can better understand her letter, which went on to explain that the English would do everyone a favor, saving them all much pain, were they to abandon Orléans and France itself according to God's will.

Her letter is astonishing.

She concluded it with a prophetic warning[35] to the English commander,

You, Duke of Bedford, the Maid prays and enjoins you, that you do not come to grievous hurt. If you will give her satisfactory pledges, you may yet join with her, so that the French may do the fairest deed that has ever yet been done for Christendom. And answer, if you wish to make peace in the City of Orleans; if this be not done, you may be shortly reminded of it, to your very great hurt. Written this Tuesday in Holy Week, March 22nd, 1428.

At her Trial of Condemnation at Rouen under the English, this letter was presented as incriminating evidence of witchcraft.[36]

“Do you know this letter?” “Yes, excepting three words. In place of ‘give up to the Maid,’ it should be ‘give up to the King.’ The words ‘Chieftain of war’ and ‘body for body’ were not in the letter I sent. None of the Lords ever dictated these letters to me; it was I myself alone who dictated them before sending them. Nevertheless, I always shewed them to some of my party."

Then, without any prompting or context, she continued,[36]

"Before seven years are passed, the English will lose a greater wager than they have already done at Orlėans; they will lose everything in France. The English will have in France a greater loss than they have ever had, and that by a great victory which God will send to the French."

"How do you know this?"

"I know it well by revelation, which has been made to me, and that this will happen within seven years; and I am sore vexed that it is deferred so long. I know it by revelation, as clearly as I know that you are before me at this moment."

"When will this happen?"

"I know neither the day nor the hour."

"In what year will it happen?"

"You will not have any more. Nevertheless, I heartily wish it might be before Saint John’s Day."[37]

The prediction came on March 1, 1431. Six years and six months later, September of 1437, Paris was delivered to the French through the Treaty of Arras, which ended the English alliance with the Duke of Burgundy and from which the English would never recover.[38] Skeptical historians will point out the English presence in France continued for another fifteen years, which is ridiculous, as the English cause was lost with the Burgundian defection. Paris was the endgame, the "greater loss" that Joan had predicted. In 1449 the French retook Rouen, where Joan was martyred, and in 1453 the English suffered a final defeat at the Battle of Castillon, which ended three hundred years of English control of southwestern France. Those later victories were only possible with the Burgundian realignment at the Treaty of Arras, which was only made possible by Joan's military and political victories at Orléans and Rheims.

Outside of her declarations regarding Orleans and the crowning of the Dauphin, this prophesy is her most significant -- and one that no one would or could have contemplated at the time, when the English were reinvigorated by her capture and had Henry VI crowned at Paris later in the year after her execution.

Upon Joan's capture, the Duke of Burgundy issued a public acclamation of victory, announcing,

‘Very dear and well-beloved, knowing that you desire to have news of us, we[39] signify to you that this day, the 23rd May, towards six o’clock in the afternoon, the adversaries of our Lord the King[40] and of us, who were assembled together in great power, and entrenched in the town of Compiègne, before which we and the men of our army were quartered, have made a sally from the said town in force on the quarters of our advanced guard nearest to them, in the which sally was she whom they call the Maid, with many of their principal captains .... and by the pleasure of our blessed Creator, it had so happened and such grace had been granted to us, that the said Maid had been taken ... The which capture, as we certainly hold, will be great news everywhere; and by it will be recognized the error and foolish belief of all those who have shewn themselves well disposed and favourable to the doings of the said woman. And this thing we write for our news, hoping that in it you will have joy, comfort, and consolation, and will render thanks and praise to our Creator, Who seeth and knoweth all things, and Who by His blessed pleasure will conduct the rest of our enterprizes to the good of our said Lord the King and his kingdom, and to the relief and comfort of his good and loyal subjects.

We see just how important was Joan's capture to the English and Burgundians: if she is not of divine intervention, they reasoned, then her successes were not legitimate, including, by reference to the English King, the coronation Joan engineered of the French King. Royal legitimacy relied on faith in God's plan, so Joan's capture justified the English cause. The next year, after Joan's execution, the English king Henry VI was coronated at Paris in an elaborate ceremony as Henry II, King of France. It was not just English assertion of the Treaty of Troyes, in which Charles VI yielded the French throne to the English upon his death, it was the English declaration of victory over the Maid. Ultimately, the English-Burgundian alliance would unravel, but, meanwhile, following Joan's capture the French, too, yielded to the theory that her capture marked, for France, her loss of divine order, falling to episodic cat-and-mouse play, both militarily[41] and diplomatically[42], hoping to weaken the English while luring the Burgundians to their side. At the time of Joan's death, it had yielded no results. After her death, the strategy continued, and French military actions were focused on consolidation and not advance, defense.[43] Yet Joan's prophesy unfolded.

As the English-Burgundian alliance unwound, the English King returned home, the English leadership lost confidence, and the French under Joan's old warriors started taking more and more land, especially around Paris. In 1435, with the death of the English Duke of Bedford, the Burgundians abandoned the alliance and signed the Treaty of Arras with the French. Soon after, the citizens of Paris opened the city gates to the Bastard of Orleans and the French army. While it took another twenty years for the end of the Hundred Years War, the outcome by then was sealed, and Charles VII was able to not just consolidate his realm, but reorganize it politically and militarily, significantly contributing to the creation of the modern state in France.

At Rouen on March 1, 1431, when Joan predicted an English defeat in France, she was neither prophet nor liar to both English and French officialdom. Whatever she meant to the warring sides now, Orleans was saved and the King of France coronated. Her job was done. link=File:Treaty_of_Troyes_cropped.jpg|thumb|Path from Chinon to Rheims (wikiepdia, cropped) Having liberated Orleans and then leading the French army across France to clear the way for the Dauphin's coronation at Rheims, to both sides Joan was either a witch or a prophet -- possessed by fiends, or of God.

At Joan's presentation to the Dauphin at Chinon, the Archbishop of Embrun, Jacques Gélu, warned the Dauphin to be careful with a peasant girl from a class that is "easily seduced." After Orleans, the Bishop had a change of heart. Applying the formula of the Evangelist, "by their fruits ye shall know them," he wrote,

We piously believe her to be the Angel of the armies of the Lord.[44]

and he advised the Dauphin,

do every day some deed particularly agreeable to God and confer about it with the maid.[45]

Whatever reservations the French clerics had held about her before Orléans turned after the battle either to acknowledgement of her as emissary of God, such as we see from Gélu and his fellow Bishop, Jean Gerson, who immediately wrote an apologia for the Maid, or, in the case of the Archbishop of Reims and newly installed Chancellor of France, Regnault de Chartres, acquiescence to events that were beyond his control.

However, detraction is easier to sustain than faith, so the English held to their hatred of Joan longer than did the French hold confidence in her. Following the coronation of Charles VII, with Joan at the height of her popularity, the Chancellor, whose goal was ever reconciliation with the Burgundian faction, not its defeat, worked to undermine her. For him, the Maid had at best served to put the issue on the table, but most inconvenient was all this insistence on taking Paris, which was a Burgundian property.[46]

The Chancellor did not want an attack upon Paris, which is why immediately after the coronation of Charles VII, which he administered as Archbishop of Rheims, he went to Saint Denis to negotiate a truce with the English to work around all this trouble Joan had caused. Talk of the Maid as a living Saint was most inconvenient for these purposes. Thus, upon her capture by the Burgundians in May of 1430, de Chartres was downright enthusiastic, announcing publicly to his diocese:

God had suffered that Joan the Maid be taken because she had puffed herself up with pride and because of the rich garments which she had taken it upon herself to wear, and because she had not done what God had commanded her, but had done her own will.[47]

Gerson had died by then, so we can't know his reaction. But Gélu's diocese issued prayers for her release, including,[48]

that the Maid kept in the prisons of the enemies may be freed without evil, and that she may complete entirely the work that You have entrusted to her.

Nevertheless, it was de Chartres who controlled French policy, and despite regular Burgundian duplicity he kept trying to negotiate a settlement. With only minor battles and outright defeats that followed the coronation, Joan's utility and legitimacy faded -- as did de Chartre's need to put up with her.

Historians have attributed Charles' treatment of Joan after his coronation to cynicism and opportunism. I'm not convinced, as he was subject to the machine as much as he was its head. He ended up playing both sides, letting Joan go forth against the English and Burgundians while withholding the resources she needed to prosecute the program. Joan's capture, which was a direct consequence of the French transition from Joan's aggression to the Chancellor's diplomacy, became the excuse to abandon her program altogether.

For their part, the English and Burgundians knew full well what this young woman had done, and the danger she still posed.[49] Although after her capture Joan was no longer a military threat, the coronation of Charles VII was a deep wound that could be healed only by delegitimizing the event by delegitimizing its author, Joan. The Burgundian clerics centered mostly at Paris faced the same problem, and so were most happy to serve as the instrument of recovery for the English. By ingratiating themselves to the English with the needed ecclesiastic stamp of heresy upon Joan, the clerics at the University aimed to elevate themselves and the French Assembly to the level of the English Parliament.[50] Modern historians emphasize these political machinations[51] as the primary motive for Joan's Trial at Rouen.

One may wonder, though, that it is not possible to maintain at once personal ambition and sincere belief, especially when the two affirm one another. Thus did de Chartres justify undermining Joan; thus did the Paris clergy justify her trial; thus did the English desperately need her denunciation; thus did the English Earl of Warwick demand that, when Joan fell dangerously sick in prison, he ordered the doctors to do whatever they could to sustain her:[52]

as the King would not for anything in the world, that she should die a natural death; she had cost too dear for that; he had bought her dear, and he did not wish her to die except by justice and the fire.”

And thus did the English Duke of Bedford, several years later, yet blame his troubles in France on Joan, writing to his King,

a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there [at Orleans] in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadded believe, and of unlevefull doubte that thei hadded of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fals enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the mobre of youre people.[53]

Barker claims that Bedford was merely casting blame upon "the Pucelle" to excuse his own poor performance. Indeed, he submitted a "written statement he had before given to the King in defence of his conduct in the government of France", explaining:[54]

he then recapitulates the services which he had rendered at the commencement of the wars in that kingdom after the death of King Henry the Fifth up to the time of the siege of Orleans ... and ascribes his subsequent want of success to a lack of sad belief and of unlawful doubt that the people had of a disciple and limb of the fiend called ‘the Pucelle’- that used false enchantments and sorcery; he reminds the King that he had himself come to England to explain the state of affairs in France, and used his utmost endeavours, but without success, to procure the means to carry on the war; he expresses his deep regret that that country should be lost after the great expenditure of blood and treasure which had occurred ; he advises that the revenues of the duchy of Lancaster, which had been vested in Cardinal Beaufort and others for the purpose of fulfilling the will of the late King, should be wholly employed in the defence of France...

He wasn't rationalizing that he had lost due to a witch -- this he admits -- he was asking for more money to make up for it. Bedford fully believed that Joan, who his government executed four years before, was a "fiend". Near the end of the Trial at Rouen, after reading to Joan the "Twelve Articles of Accusation" (consolidated from seventy), a priest and "celebrated Doctor in Theology,"[55] Pierre Maurice, who was deeply tied to the English, lectured Joan on the "peril" she was subjecting upon her soul:

Do not allow yourself to be separated from Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who hath created you to be a sharer in His glory ; do not choose the way of eternal damnation with the enemies of God, who daily set their wits to work to find means to trouble mankind, transforming themselves often, to this end, into the likeness of Our Lord, of Angels and of Saints, as is seen but too often in the lives of the Fathers and in the Scriptures. Therefore, if such things have appeared to you, do not believe them. The belief which you may have had in such illusions, put it away from you.

At this point in the Trial, they just wanted to do away with her, which is why they forced her into the confession and subsequent relapse upon putting back on the men's clothing. Upon that discover, the Bishop of Beauvais exclaimed to the English lord, Warwick,[56]

She is caught this time!

The Bishop, Cauchon, was entirely compromised to the English by his ambitions, but he was convinced that Joan was of the Evil One. He probably never imagined how long the trial would go, as his frustration grew with every unexpected response and retort from Joan to the best theological traps the University of Paris' finest minds could throw at her. One of the priests there who testified at the Trial of Rehabilitation recalled that her responses were inspired:[57]

When she spoke of the kingdom and the war, I thought she was moved by the Holy Spirit; but when she spoke of herself she feigned many things: nevertheless, I think she should not have been condemned as a heretic.

It's an interesting testimony coming amidst a politically-charged reassessment of a trial he had participated in twenty-four years before on behalf of the enemy, so his hedge that "when she spoke of herself" is interesting. His mixed statement shows either that he was putting her in as good a light as possible -- as regarded the King of France, who was under a reassessment as much as was Joan: justifying Joan meant justification for him. Nevertheless, de la Pierre was under oath, and we must take his testimony as such: Joan was inspired by the Holy Spirit.

The Rouen court had its way, and was unequivocal in its condemnation of Joan not just as a heretic, but as a witch, an "invoker of devils." It wasn't about her men's dress, and it wasn't about apostasy. It was all about her refusal to deny her Voices. To read the epithet placed upon a placard by the stake on which she was burned is to understand just how real her voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[58]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to the Crucifixion of the Lord himself here and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no, it wasn't. They meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from the trial,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[59]

Now we're talking! So let's re-write this historian's own epithet for Joan, only with faith and love in Christ, as Joan's canonization is to be celebrated, not used as a weapon against Joan's own faith.

They believed in Joan and made her their heroine, affirmed by Mother Church with her official and glorious canonization on May 9, 1921 and followed by State declaring July 10, her Feast Day, a national holiday.

The historical problem of (Saint?) Joan of Arc

The most prominent modern biographer of Saint Joan, Régine Pernoud (1909-1998), a medieval scholar, counsels,

Among the events which [the historian] expounds are some for which no rational explanation is forthcoming, and the conscientious historian stops short at that point.[60]

So the "conscientious historian" must contain himself to "the facts" and stick to sorting them out for description while avoiding explanation, much less inference from those facts. It's not only impossible, it's historiographically useless: I can describe the American Revolution all day long, but if I don't attributed it to a cause I have learned nothing. Same with any historical moment, from the Roman ascension to the last American election. What good is history if it just says and does not explain? (If so, the entire profession would be out of a job.) For Joan, so it is. Because her motives, actions, and outcomes are so improbable, to attribute them to anything other than divine guidance makes no sense. But since divine guidance is "ahistorical," or merely an article of faith, Joan's motives don't matter historically. Pernoud thereby dismisses them altogether, falling back upon,

The believer can no doubt be satisfied with Joan’s explanation; the unbeliever cannot.[61]

What, then, does the "unbeliever" do with the evidence? That the "unbeliever cannot" accept Joan's own explanations is an easy out from what is plain to see. But the problem is larger. Joan did experience voices and visions. If they were not real, then how to explain their effects? Such is a core Catholic tenant, drawn from the Gospel of Matthew 12:33[62], in which Jesus declares to the Pharisees,

Either declare the tree good and its fruit is good, or declare the tree rotten and its fruit is rotten, for a tree is known by its fruit.

Historians have two outs here: the first is to deny the source of Joan's Voices while admitting their effects; the second is to deny their effects. To the first strategy, historians like Pernoud step around the problem by denying the sources or even reality of her Voices, but taking their effects at face value.[63] Others follow the second and minimize Joan's historical role altogether, i.e. lesser effects.[64] Or they use both. So we hear that it was schizophrenia or moldy bread, which at least recognize that Joan heard voices.[65] Others who question the reality of the Voices must fall back on pseudo-psychological conjecture and sociological babble. For example, historian Ann Lelwyn Barstow argues that subjects of Joan's visions were those Saints with which she most closely identified and was most familiar:[66]

One gets the picture of a lively Christianity informing the mind of the young Joan through legends. well-known across Europe ... That she was visited instead [of the Virgin Mary] by Michael, Catherine and Margaret attest to the potency of their legends in Lorraine, to their particular usefulness to a young patriot in time of national distress, and their appropriateness for an independent-minded woman.

The Church in Domrémy held (and apparently still holds[67]) a statue of Saint Margaret; Saint Catherine was the patron Saint of nearby church; Saint Michael was venerated in Lorraine and was considered the defender of France; so there you have it. Given that reasoning, one may suppose that some other Saint, say, Saint Drogo, might have equally conveyed God's message to a thirteen year old in rural eastern France, as, while notoriously butt-ugly, he was from the northeast of the country and spoke French. It's nonsense. Of course, God sent the Saints that Joan already knew and trusted. To paraphrase Joan, “Do you think God has not wherewithal to select the right Saints for Joan?"[68] If Joan's visions were real, then we have perfectly explainable historical causation, including for her flustered recantation of her Voices when threatened in public humiliation before the stake. Skeptical historians point to this moment as evidence that Joan had just made it all up, ignoring that only two weeks before this demeaning public ceremony, when threated with torture she had told the court,[69]

Truly if you were to tear me limb from limb, and separate soul and body, I will tell you nothing more; and, if I were to say anything else, I should always afterwards declare that you made me say it by force.

But so goes the theory that, fatigued and confused, Joan gave the hostile and abusive English-backed court what it wanted and made up stories of the Saints, whom, it (incorrectly) holds, she had not before mentioned.[70] Similarly, it holds, both supporters and detractors of Joan were just using her for their convenience, and that the historical record itself reflects that self-interest and not the truth about Joan.[71]

To any extent they admit of Joan's role in those events, they simply cannot explain the village girl's astonishing natural and supernatural abilities.

Medieval historian Juliet Barker sees Joan's career as entirely political in terms of her own ambitions and those of those around her. As such, Barker credits the pro-French Armagnacs for using her to push their war against the English-allied Burgundians, even so as to credit the Armagnacs for having engineered not just Joan's introduction to the Dauphin but to the her ability to identify him hidden amidst the courtiers.[72] Of course there is no evidence for such trickery, but the theory does legitimately point to the Dauphin's equivocal position between the anti-Burgundian and reconciliation factions around him. The problem with the view is that is treats the Dauphin as merely going along for a ride with the Maid just to see what might happen.[73] As the Dauphin's advisor, Bishop Jean Gerson observed, allowing a girl to lead an army isn't a trial balloon. In his apologia for Joan written shortly after her victory at Orleans, he observed that to give an army to a woman isn't just crazy, it's dangerous:

"The king's council and the men-at-arms were led to believe the word of this Maid and to obey her in such a way that, under her command and with one heart, they exposed themselves with her to the dangers of war, trampling under foot all fear of dishonor. What a shame, indeed, if, fighting under the leadership of a woman, they had been defeated by enemies so audacious! What derision on the part of all those who would have heard of such an event![74]

These historians reply that the Dauphin was obsessed with prophesy, so he naturally fell to the latest seer. Or, as does Barker, the Dauphin's military situation was not as dire as Joan's "cheerleaders" have claimed, so, by implication, she wasn't the essential actor in the moment.[75] But not even Barker claims that without Joan's involvement the French would have won at Orléans. The theory is ever insufficient to explain the events. Unlike historians, the actors of Joan's day had to to decide: either Joan acted on voices of God -- or of Satan. There was no in between. Just ask the English and Burgundians who knew full well what this young woman had done and why.[49] The rage of the ecclesiastical Court and its English backers that condemned her is in inverse proportion to the glory of Joan's visions and the reality Joan and her people understood them to be. To read the epithet the English placed upon a placard by the stake is to understand just how real her voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[58]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to a typology of the crucifixion of the Lord himself and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation of Joan is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no -- they meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from the trial,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[59]

All our skeptics can do is to question the motives of these testimonies, saying that de la Pierre and Ladvenu were covering up their own shameful involvement in the Trial for heresy. Perhaps, but even if true, the testimony affirms Joan's innocence. The details, though, are hard to ignore: "her heart remained intact", "the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal" -- memory works this way, not imagination.

These historians engage in the same process as writing a book on the life of Jesus as a non-believer.[76] You'd get caught up in denying the Lord's virgin birth, denying the miracles, denying the resurrection, and, ultimately, as some do, denying his historical presence altogether -- understandably so, as the story of Christ makes no sense without his divinity.[77] Actually, Thomas Jefferson did just this, conducting a now obscure and theologically meaningless cut and paste job on the New Testament, from which he extracted the angels, prophesies, miracles, and the Resurrection.[78] Accepting the historicity of Christ without the miraculous requires denying the authenticity of the Gospels and attributing them to post hoc contrivances.[79] It gets messy and, frankly, serves merely to deny Christ rather than understand him.

And with Joan of Arc that's where our historians land. Pernoud denies that Joan was, in CS Lewis' terms[80], a madman, but neither was she divinely guided. So all we have left is that she was a liar -- and thus of the devil, something Pernoud, a deep admirer of Joan, never broaches, although the English put her to death for it.

Lewis prefaces his argument about Christ's divinity by noting,

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say.

The logic applied to Joan goes the same way: treating her merely as an historical character debases what she was and did. So it is that Pernoud concludes that when "confronted by Joan" all we can do is to "admire" her, as the common people have since the 15th century, for "in admiring [they] have understood her":

They canonised Joan and made her their heroine, while Church and State were taking five hundred years to reach the same conclusion.[81]

That's as close as Pernoud will come to an historical "saint" Joan -- that she was "canonized" in the hearts of her countrymen.

While affirming Joan's popular canonization, Pernoud incorrectly claims that the "Church and State" didn't understand her until 1921, forgetting that Joan's "Rehabilitation Trial" and its declaration of her innocence was, in Pernoud's own words, "in the name of the Holy See."[82] This historian ought to know that very few of the laity were canonized before the 20th century, including the 16th century Sir Thomas More, who wasn't canonized until 1935, and despite great hostility for it from the Anglican Church. Saint Joan's canonization underwent a similar dynamic, delayed by the intervention of the French Revolution and subsequent 19th century European anti-clericalism and anti-monarchism.

Free of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not, Pernoud's historiography leads her to this sentimentalized and historically insufficient view of Joan's contemporaries and her legacy. So we get these dumb, dull statements of Joan's legacy, such as at end of one of her books,

It remains true that, for us, Joan is above all the saint[83] of reconciliation—the one whom, whatever be our personal convictions, we admire and love because, over-riding all partisan points of view, each one of us can find in himself a reason to love her.[84]

That's no better than this, from the collective wisdom of contributors to the "Joan of Arc" entry at Wikipedia:

Joan's image has been used by the entire spectrum of French politics, and she is an important reference in political dialogue about French identity and unity.[85]

So Joan is in the eye of the beholder.

My larger concern here is that a historiography that frees itself of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not leads to a misreading of the facts. We cannot comprehend the motives and choices of Joan herself, much less those of her followers and detractors without it.

But what is equally bewildering is that these historians mostly ignore the most thorough, considered, and balanced investigation into Joan, by the Vatican itself. On consideration for beatification and canonization, the Church investigates the case, and thoroughly, assigning advocates for and against the candidate.[86] We'll get into it later, but there were serious charges against her, including waging war on a Holy Day, her disobedience to her Voices, questions about her purity, and her reluctance to be burned to death, which was considered "unsaintly."

Virgin Joan

To the modern, especially academic, audience, the matter of Joan's virginity is understood as a male obsession or instrument of the patriarchy, or whatever they say about these things. One theory holds that Joan called herself "the virgin" in order to fend off the soldiers around her,[87] while another claims she wanted to "emphasize her unique identity".[88] But to both Joan and her accusers at the Trial of Condemnation, the matter of her virginity presented a deadly serious theological question: if she was truly an ambassador from God then she had to be a virgin; if not, as the English-backed court tried to prove, she was a witch, for a virgin, it was understood, was incorrupt of Satan's reach.

As the 19th century French historian Jules Michelet's explained,

The archbishop of Embrun [Jacques Gélu], who had been consulted, pronounced similarly; supporting his opinion by showing how God had frequently revealed to virgins, for instance, to the sibyls, what he concealed from men; how the demon could not make a covenant with a virgin and recommending it to be ascertained whether Jehanne were a virgin.[89]

The French and, later, the English-supported Burgundians, submitted her to the physical test conducted by ladies who affirmed her purity. The French, who first examined Joan's theological purity, questions to which she answered consistently, simply, and strenuously, concluded, "The maid is of God."[90] They found nothing impure in her, which was important for fulfillment of the legend that Joan herself invoked, such as she told her uncle, Durand Lexart, and which had become current as she made her way to meet the prince of France, the Dauphin[91]:

"Has it not been said that France will be lost by a woman[92] and shall thereafter be restored by a virgin?[93]

At the Condemnation Trial under the English at Rouen, Joan was pressed several times on her virginity, which had already been affirmed by ladies of the Burgundian court. Her accusers wouldn't let it go. Having caught on to a story about a supposed marriage when she was younger, they pressed her,

“When you promised Our Saviour to preserve your virginity, was it to Him that you spoke?”

“It would quite suffice that I give my promise to those who were sent by Him—that is to say, to Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret.”

“Who induced you to have cited a man of the town of Toul on the question of marriage?”

“I did not have him cited; it was he, on the contrary, who had me cited; and then I swore before the Judge to speak the truth. And besides, I had promised nothing to this man. From the first time I heard my Voices, I dedicated my virginity for so long as it should please God; and I was then about thirteen years of age. My Voices told me I should win my case in this town of Toul.”

Argued by Joan herself before the magistrate at Toul, the marriage claim was dismissed. She was neither bequeathed to nor married the man, and so there was no compromise of Joan for the court at Rouen to exploit. It's an odd part of her story, but one that importantly informs much about Joan. First, either her father, or some guy, or both, tried to marry her off to him[94]. A young girl like Joan would normally have no say in the matter: instructed by her voices, she stood it down. Secondly, it's among or even the very first direct event upon which her voices guided her, and she believed and obeyed. Well convinced of her larger mission to "go to France," Joan wouldn't let this claim upon her get in her way. One wonders, even, why it happened, if not to disrupt her trajectory.

Getting no where with that topic, which had the dual purpose of accusing her of disobedience to her parents and to suggest that she was not a virgin, her persecutors at the Trial of Condemnation moved on, focusing on her use of men's clothing. But they couldn't let the matter of her virginity go. Five days later, the questions returned to,[95]

“Was it never revealed to you that if you lost your virginity, you would lose your happiness, and that your Voices would come to you no more?”

“That has never been revealed to me.”

“If you were married, do you think your Voices would come?”

“I do not know; I wait on Our Lord.

This line of questioning becomes rather sinister when Joan is later on tricked, compelled, rather, into wearing women's clothes in prison, which turned her into a target of rape by her English guards.[97] She knew that men's clothing that she insisted on wearing kept her safe from the possibility, so the Rouen Court was playing into that situation, whereby, were she raped they could say she no longer had valid visions. But she refused to answer that question ("I wait upon Our Lord") and, thankfully, while attacked at one point by the guards, it seems she was not actually violated. It did become the very point upon which she was executed.

As for Joan's own view of her virginity, it was what and who she was, and she promised the Saints that she would stay chaste. Whatever the historians' argument that pucelle means maid or virgin or both, we can see from Joan's perspective that her virginity was essential to her mission both as sign of purity and, more importantly, selfless dedication to the Lord.[98]

Saint Paul explains it in 1 Corinthians 7:34:

An unmarried woman or a virgin is anxious about the things of the Lord, so that she may be holy in both body and spirit.

Catholic Joan

Given most biographies and depictions of Saint Joan, it's rather hard to appreciate her Catholicism -- it is simply ignored or denied. Such historians "contextualize" her amidst a backwards, superstitious, Middle Ages Catholic world, perhaps recognizing that Joan was more devout -- to a backwards religion, apparently -- than were others. Even there, the historical snobbery ever leaks in, as if others less devout than Joan weren't actually believers, just followers of some tradition. Going through the literature, I constantly run into dismissals of or end runs around Catholicism, such as not using "Saint" before a name and "Christian hagiography".[99] Worst of all are those histories that place Joan amidst a syncretic mysticism, a mix of "medieval Catholicism", "folk religion", and paganism, and so attribute her experiences to it.[100]

Saint Joan of Arc -- drop the "Saint," if you will -- Joan of Arc makes no sense unless we recognize her Catholicity. She was fundamentally, authentically and thoroughly Catholic.

John Mooney's 1897 biography, written during the push for her beatification, refreshingly does not question Joan's Catholicism. In the 1919 edition, issued just after the Great War in which Joan's rallying example helped save France, and just before Joan's canonization, the Introduction by Catholic author Blanche Mary Kelly gets it right:[101]

Without the Catholic Faith, she is inexplicable. More than on her sword, she relied on the Mass; more than bread, the sacraments were her sustenance.

Three Masses marked a good day for Joan.[102] She was seen constantly in prayer, and asked for Confession whenever possible. Father Jean Massieu recalled that during her trial at Rouen Joan dropped to the floor at the doors of a chapel when told that a consecrated Host lay inside:

Once, when I was conducting her before the Judges, she asked me, if there were not, on her way thither, any Chapel or Church in which was the Body of Christ. I replied, that there was a certain Chapel in the Castle. She then begged me to lead her by this Chapel, that she might do reverence to God and pray, which I willingly did, permitting her to kneel and pray before the Chapel; this she did with great devotion. The Bishop of Beauvais was much displeased at this, and forbade me in future to permit her to pray there.

and,

And, besides, as I was leading Jeanne many times from her prison to the Court, and passed before the Chapel of the Castle, at Jeanne’s request, I suffered her to make her devotions in passing; and I was often reproved by the said Benedicite, the Promoter, who said to me “Traitor! what makes thee so bold as to permit this Excommunicate to approach without permission? I will have thee put in a tower where you shall see neither sun nor moon for a month, if you do so again.”

The English-backed Bishop of Beauvais' anger at her prayer before the chapel was recognition of her Catholic authenticity, which it was his job to deny in order to put her to death. We can never know if he actually believed her to be a witch and a heretic, although we have plenty of evidence to demonstrate bad faith in his motives. Either way, he could not allow for her presentation as a true and faithful Catholic, which is why her worship, on learning that the Lord was present in the chapel, so angered him.

Historians say Joan was merely conforming to norms of her day. It's an interesting point that, for, even if just a social norm, Joan's Catholic devotion well-surpassed that of those around her. Not only did witnesses affirm her distinct piety, she brought them into it themselves. From her soldiers and fellow officers, to the people of France, she affirmed the faith for believers and converted many, including, most famously, one of her captains, La Hire, who became known for prayer before battle, which he learned from Joan.[104]

The cleric Séguin de Séguin recalled,[105]

When she heard any one taking in vain the Name of God, she was very angry; she held such blasphemies in horror: and Jeanne told La Hire, who used many oaths and swore by God, that he must swear no more, and that, when he wanted to swear by God, he should swear by his staff. And afterwards, indeed, when he was with her, La Hire never swore but by his staff.

Her enemies teach us, as well. With the evidence before us from antagonistic points of view, we can learn much about Joan from the attacks upon her. The English-backed Rouen ecclesiastical court pushed her on orthodoxy.

The formal charges against her started with a claim of authority from the court,[106]

Article I. And first, according to Divine Law, as according to Canon and Civil Law, it is to you, the Bishop, as Judge Ordinary, and to you, the Deputy, as Inquisitor of the Faith, that it appertaineth to drive away, destroy, and cut out from the roots in your Diocese and in all the kingdom of France, heresies, witchcrafts, superstitions, and other crimes of that nature; it is to you that it appertaineth to punish, to correct and to amend heretics and all those who publish, say, profess, or in any other manner act against our Catholic Faith: to wit, sorcerers, diviners, invokers of demons, those who think ill of the Faith, all criminals of this kind, their abettors and accomplices, apprehended in your Diocese or in your jurisdiction, not only for the misdeeds they may have committed there, but even for the part of their misdeeds that they may have committed elsewhere, saving, in this respect, the power and duty of the other Judges competent to pursue them in their respective dioceses, limits, and jurisdictions. And your power as to this exists against all lay persons, whatever be their estate, sex, quality, and pre-eminence: in regard to all you are competent Judges.

The statement is a rote declaration of authority and purpose, likely not much different from any other such trial, especially the mandate to stamp out "sorcerers, diviners", etc. The problem for the court in this case is that there was no evidence of Satan's works upon Joan outside of her having defeated the English in battle. Even the matter of her clothing was theologically not difficult to dismiss, as had the bishops who had investigated her on behalf of the Dauphin at Poitiers.[107]

The Rouen court did its homework. They sent investigators to her hometown, who came back with stories from her village of charms and fairies, from which they inferred that Joan, too, believed in them (modern courts call this "speculative" as opposed to "circumstantial" evidence[108]). Worse for them, they were never able to pierce the consistent Catholic logic of her replies to their examinations. The worst they could find was that she had kissed the feet of Saints, who, by Church dogma, were understood not to have bodies.

This is a girl whose mother taught her to recite in Latin the Our Father, Ave Maria, and Credo prayers. Her religious upbringing was entirely orthodox. Her devoutness to it irrepressible. Her military standard read, "Jhesus Maria," and her final words were "Jesus" repeated as the flames consumed her and while staring at a cross she asked be held before her.

To Article I of the formal charges, Joan replied,

I believe surely that our Lord the Pope of Rome, the Bishops, and other Clergy, are established to guard the Christian Faith and punish those who are found wanting therein: but as for me, for my doings I submit myself only to the Heavenly Church— that is to say, to God, to the Virgin Mary, and to the Saints in Paradise. I firmly believe I have not wavered in the Christian Faith, nor would I waver.

Joan was simply and thoroughly Catholic.

Joan and the Saints

The standard modern histories go with Joan's testimony and experiences about her Voices without affirming their reality. Presented with the final indictment from the Trial of Condemnation, which denied her visions, Joan instead resoundingly affirmed them:[109]

As firmly as I believe Our Saviour Jesus Christ suffered death to redeem us from the pains of hell, so firmly do I believe that it was Saint Michael and Saint Gabriel, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret whom Our Saviour sent to comfort and to counsel me.

That still leaves us with the problem of the effects of the Voices, i.e. divine intervention.

Ultimately, the ecclesiastical court at Rouen condemned Joan for reneging on her vow to wear women's clothes,[110] which was a setup. But her visions drove them crazy, and they spent much time challenging and arguing with her about her encounters with the Saints. She answered everything plainly, which, again, drove them crazy.

For a believer, what an an incredible opportunity to learn about the Saints! For example,[111]

“Was Saint Gabriel with Saint Michael when he came to you?”

“I do not remember.”

“Since last Tuesday, have you had any converse with Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret?”

“Yes, but I do not know at what time.”

“What day?”

“Yesterday and to-day; there is never a day that I do not hear them.”

“Do you always see them in the same dress?”

“I see them always under the same form, and their heads are richly crowned. I do not speak of the rest of their clothing: I know nothing of their dresses.”

“How do you know whether the object that appears to you is male or female?”

“I know well enough. I recognize them by their voices, as they revealed themselves to me; I know nothing but by the revelation and order of God.”

“What part of their heads do you see?”

“The face.”

“These saints who shew themselves to you, have they any hair?”

“It is well to know they have.”

“Is there anything between their crowns and their hair?”

“No.”

“Is their hair long and hanging down?”

“I know nothing about it. I do not know if they have arms or other members. They speak very well and in very good language; I hear them very well.”

“How do they speak if they have no members?”

“I refer me to God. The voice is beautiful, sweet, and low; it speaks in the French tongue.”

“Does not Saint Margaret speak English?”

“Why should she speak English, when she is not on the English side?”

Just magnificent.

So where historians can simply dismiss her testimony as, well, something, taking it on face-value without affirming their reality, Joan here gives us a unique view into the experiences of a real mystic.

The English-backed court of course, was entirely antagonistic to her experiences, and reoriented her testimony and their questions constantly towards the accusations of witchcraft, such as the legend of a "Fairy Tree" at her hometown, Domrémy and mandrakes, a flowering plant which sorcerers were supposed to have used, and which were commonly kept by peasants as charms. Evidently their investigation into Joan's hometown found that mandrakes were used there, which would be affirmed by the village priest who in April 1429, after Joan had already departed, preached against them.[112] After Joan declares,

“Do you want me to tell you what concerns the King of France? There are a number of things that do not touch on the Case. I know well that my King will regain the Kingdom of France. I know it as well as I know that you are before me, seated in judgment. I should die if this revelation did not comfort me every day.”

the questioner turns away from that rather uncomfortable, for the English and their allies, prophesy, then turns to a textbook leading question regarding the mandrakes:

What have you done with your mandrake?

Joan had no counsel, so no one was there to point out that the question assumed she owned one. But no matter for Joan, who swatted it back at them,

I never have had one. But I have heard that there is one near our home, though I have never seen it. I have heard it is a dangerous and evil thing to keep. I do not know for what it is [used].[113]

Getting nowhere with the mandrake, the questioners turned back to the Saints:

“In what likeness did Saint Michael appear to you?”

“I did not see a crown: I know nothing of his dress.”

“Was he naked?”

“Do you think God has not wherewithal to clothe him?”

“Had he hair?”

“Why should it have been cut off? I have not seen Saint Michael since I left the Castle of Crotoy. I do not see him often. I do not know if he has hair.”

“Has he a balance?”[114]

“I know nothing about it. It was a great joy to see him; it seemed to me, when I saw him, that I was not in mortal sin. Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret were pleased from time to time to receive my confession, each in turn. If I am in mortal sin, it is without my knowing it.”

Always deferring to another topic when the prior line of questioning got them nowhere, and seizing on any point Joan made that could be twisted or used against her, her interrogators must have nearly jumped from their seats in glee at this one:[115]

When you confessed, did you think you were in mortal sin?

But they were up against a Saint. Joan replied,

I do not know if I am in mortal sin, and I do not believe I have done its works; and, if it please God, I will never so be; nor, please God, have I ever done or ever will do deeds which charge my soul!

The next day, they went straight at her visions. The scribe noted that she had previously testified that Saint Michael "had wings" but nothing about the forms of Saints Catherine and Margaret. The scribe noted,[116]

Afterwards, because she had said, in previous Enquiries, that Saint Michael had wings, but had said nothing of the body and members of Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret, We asked her what she wished to say thereon.

Joan responded,

“I have told you what I know; I will answer you nothing more. I saw Saint Michael and these two Saints so well that I know they are Saints of Paradise.”

“Did you see anything else of them but the face?”

“I have told you what I know; but to tell you all I know, I would rather that you made me cut my throat. All that I know touching the Trial I will tell you willingly.”

“Do you think that Saint Michael and Saint Gabriel have human heads?”

“I saw them with my eyes; and I believe it was they as firmly as I believe there is a God."

“Do you think that God made them in the form and fashion that you saw?”

“Yes.”

“Do you think that God did from the first create them in this form and fashion?”

“You will have no more at present than what I have answered.”

Time to move on, then, now to whether her voices told her she will escape, another point they used against her as she had attempted to escape from her original capture by the Burgundians. We also learn about Joan's relationship with the Saints, not just her interactions of guiding, consoling, and redirecting her. After being threatened with torture, Joan turned to them:[117]

I asked counsel of my Voices if I ought to submit to the Church, because the Clergy were pressing me hard to submit, and they said to me: ‘If thou willest that God should come to thy help, wait on Him for all thy doings.’ I know that Our Lord hath always been the Master of all my doings, and that the Devil hath never had power over them. I asked of my Voices if I should be burned, and my Voices answered me: ‘Wait on Our Lord, He will help thee.’

Joan knew full well the consequences of condemnation for heresy, so the stake was on her mind, likely throughout the ordeal. The court brought it up to her directly, though, in the public assembly at the cemetery of St. Ouen, where she was read the documents of abjuration.[118] After his public sermon in which he admonished Joan, the priest Érard, who was as violently against Joan as any, including the Bishop of Beauvais, read the charges that she was to abjure, adding that were she not to admit it, she'd burn. From the testimony at the Trial of Rehabilitation by the scribe, Father Jean Massieu,[119]

To which Jeanne replied, that she did not understand what abjuring was, and that she asked advice about it. Then Érard told me to give her counsel about it. After excusing myself for doing this, I told her it meant that, if she opposed any of the said Articles, she would be burned. I advised her to refer to the Church Universal as to whether she should abjure the said Articles or not. And this she did, saying in a loud voice to Érard: “I refer me to the Church Universal, as to whether I shall abjure or not.” To this the said Érard replied: “You shall abjure at once, or you shall be burned.” And, indeed, before she left the Square, she abjured, and made a cross with a pen which I handed to her.

There is much argument as to whether or not in the abjuration Joan knowingly denied the Saints.[120] We know she had earlier disobeyed her Voices when she leapt from captivity from the Burgundians,

About four months. When I knew that the English were come to take me, I was very angry; nevertheless, my Voices forbade me many times to leap. In the end, for fear of the English, I leaped, and commended myself to God and Our Lady. I was wounded. When I had leaped, the Voice of Saint Catherine said to me I was to be of good cheer, for those at Compiègne would have succour.[121] I prayed always for those at Compiègne, with my Counsel.

So perhaps facing the threat of the fire -- understandably so -- she signed the papers. A few days after her abjuration, she was brought back to the Rouen court for a "relapse" trial for having put back on the men's garments. It gave the court the opportunity to not only accuse her of breaking her vow to wear women's clothes but to force her into a denial of her recantation of the Saints. Now imminently facing the stake, Joan admitted that by signing the abjuration document she had betrayed the Saints:

“They said to me: ‘God had sent me word by St. Catherine and St. Margaret of the great pity it is, this treason to which I have consented, to abjure and recant in order to save my life! I have damned myself to save my life!’ Before last Thursday, my Voices did indeed tell me what I should do and what I did on that day. When I was on the scaffold on Thursday, my Voices said to me, while the preacher was speaking: ‘Answer him boldly, this preacher!’ And in truth he is a false preacher; he reproached me with many things I never did. If I said that God had not sent me, I should damn myself, for it is true that God has sent me; my Voices have said to me since Thursday: ‘Thou hast done a great evil in declaring that what thou hast done was wrong.’ All I said and revoked, I said for fear of the fire.”

“Do you believe that your Voices are Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret?”

“Yes, I believe it, and that they come from God.”

Much has been made of this supposed recantation or betrayal of the Voices. It's rather simple, though,

All I said and revoked, I said for fear of the fire.

And now, as she knew full well, she was going to be led to the fire. There's no betrayal in that: rather a correction and support for what would follow, which would have followed, anyway, had during the sermon she had "Answer[ed] him boldly, this preacher!"[122] Neither Joan nor her Voices had let one another down.

Saint Catherine

Joan's virginity importantly signaled her connection to Saint Catherine, the virgin martyr. As did Joan, Saint Catherine precociously presented herself to a king, in Catherine's case, the Roman Emperor Maxentius, and boldly declared God's message. As did the sitting French ruler, the Dauphin, to Joan, Maxentius ordered an inquiry into Catherine by the emperor's finest theologians and philosophers. When these smartest men in the room were confounded by Catherine's theological arguments, the emperor had her imprisoned and tortured. Joan was also submitted to another but entirely antagonistic inquiry at the British-controlled French ecclesiastical Court at Rouen that condemned her but which she confounded with marvelous simplicity and irrefutable logic.

Next for Saint Catherine, Maxentius demanded that Catherine marry him and put her to death when she refused.[123] The parallel for Joan continues, as she was put to death after refusing a conciliatory but compromising offer from the court at Rouen, which is when she agreed to put on women's clothing, and is condemned for subsequently abandoning them for men's trousers.[124]

If you look up Saint Catherine you will see claims that she never existed, or that the stories about her are medieval fabrications.[125] But that's not how God works. God love types and bookends, and Saint Joan is clearly a "type" of Saint Catherine: when the Dauphin ordered the Church inquiry, no one was thinking, "My, that's just what happened to Saint Catherine!" And no such thoughts arose when the court at Rouen tried to force her into admission of heresy by showing her torture machines and then tricking her into signing a document to renounce her visions and to go back to wearing women's clothes -- at which point her guards threatened to rape her.[126] Therein is the very typology of Saint Catherine.

Saint Margaret

She was also visited by Saint Margaret, another virgin and maiden martyr who was killed after refusing to marry a Roman governor and to renounce her faith. Historians point out that Joan may have related herself to Saint Margaret over an incident in which Joan was accused by a man from her region of having broken a vow of marriage. She successfully argued to a magistrate that there was no such betrothal, and the accusation was dismissed. The typological connection holds here, although I don't see it as significant as the betrayals she suffered from Charles VII and, especially, the English-backed court at Rouen.

Saint Margaret's typology for Joan follows more closely Saint Margaret's vows of virginity, her refusal to renounce her faith in a public trial, and enduring imprisonment and torture. (Oh, and Saint Margaret spent her youth as a shepherd.) Additionally, Saint Margaret was burned, and that unsuccessful, thrown into a vat of boiling water, escaping both unharmed, so her martyrdom came at beheading. Joan was burned, of course, but her heart would not, as testified by the English guard who oversaw her execution.[127] Legend holds that while imprisoned, Saint Margaret was devoured by Satan in the form of a dragon, from which she was expelled due to the Cross she held. Here, again, is an important connection to Joan on the stake, as she asked that a cross be held before her and she repeated "Jesus" until she expired.

As with the accusation of engagement, Joan's visions started well before all these events, so she was not mimicking Saints Catherine and Margaret, and nor could she have anticipated those connections when she started out. Instead, she was, at their guidance, fulfilling their types.

Saint Michael the Archangel