Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle): Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

These pages present a Catholic view of Saint Joan of Arc that is consistent with the vetted historical record. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of her, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her life and legacy. | These pages present a Catholic view of Saint Joan of Arc that is consistent with the vetted historical record. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of her, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her life and legacy. | ||

The analysis here starts with faith not doubt, thus Joan's experiences and visions (which I will call her "Voices") are assumed as real.<ref name=":12">As opposed to skeptical treatments of Joan that merely assume that her visions were not divine; similarly, these pages will not automatically assume a divine nature for everything she did nor what she was said to have done: the approach here is faithful yet cautious.</ref> As opposed to skeptical treatments of Joan that | The analysis here starts with faith not doubt, thus Joan's experiences and visions (which I will call her "Voices") are assumed as real.<ref name=":12">As opposed to skeptical treatments of Joan that merely assume that her visions were not divine; similarly, these pages will not automatically assume a divine nature for everything she did nor what she was said to have done: the approach here is faithful yet cautious.</ref> As opposed to skeptical treatments of Joan that begin from doubt, these pages accept their divine nature, which, applied prudently, enables important historical, typological, and scriptural connections to Joan's life and acts that otherwise go unconsidered. The approach here is faithful yet cautious, open but not credulous. | ||

This discussion of Saint Joan is analysis not narrative. Although the narrative is presented, the approach here is thematic not strictly chronological. To review a straight chronology of her life, please see the [[Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)/Joan of Arc Timeline|Joan of Arc Timeline]] or find a good narrative treatment of her from the [[Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)/Joan of Arc bibliography|Joan of Arc bibliography]]. | This discussion of Saint Joan is analysis not narrative. Although the narrative is presented, the approach here is thematic not strictly chronological. To review a straight chronology of her life, please see the [[Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)/Joan of Arc Timeline|Joan of Arc Timeline]] or find a good narrative treatment of her from the [[Saint Joan of Arc (Jeanne la Pucelle)/Joan of Arc bibliography|Joan of Arc bibliography]]. | ||

Revision as of 23:49, 9 March 2025

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431)

("Concerning the fact of the Maid and the faith due to her")[1]

Saint Joan of Arc called herself, Jeanne la Pucelle,[2] meaning "Joan the Maid." Her followers called her, simply, La Pucelle. Her antagonists spitefully called her "the one who calls herself the Maid" or "Joan who calls herself the Maid."[3]

Preface

These pages present a Catholic view of Saint Joan of Arc that is consistent with the vetted historical record. It reviews the facts of the life and accomplishments of Saint Joan, as well as their historical context. It offers commentary and criticism of historical and academic views of her, especially as regards the secularization and ideological contortions of her life and legacy.

The analysis here starts with faith not doubt, thus Joan's experiences and visions (which I will call her "Voices") are assumed as real.[4] As opposed to skeptical treatments of Joan that begin from doubt, these pages accept their divine nature, which, applied prudently, enables important historical, typological, and scriptural connections to Joan's life and acts that otherwise go unconsidered. The approach here is faithful yet cautious, open but not credulous.

This discussion of Saint Joan is analysis not narrative. Although the narrative is presented, the approach here is thematic not strictly chronological. To review a straight chronology of her life, please see the Joan of Arc Timeline or find a good narrative treatment of her from the Joan of Arc bibliography.

As with any valid historical analysis, this one weighs the evidence, adopts a perspective, and tests it against the historical and historiographic record. The extensive record of Saint Joan allows for cherry-picking and unsupported interpretation of witness motives, so, unlike many histories of Joan of Arc, mine will not use isolated "proof-text" to support the claims, but will instead consider all the evidence, including that which has been used to argue against, especially, Joan's Divine guidance.

Finally, as my arguments are contingent upon the larger historical context before and after the life of Saint Joan, I encourage the reader to explore the history more largely in the sources listed in the footnotes and bibliography.

Presented, as well, is the theory that Joan's mission was not to save France so much as to save Roman Catholicism.

Related pages:

- Joan of Arc Timeline

- Joan of Arc bibliography

- Kings of France and England

- Popes and antipopes

- Saint Joan of Arc glossary for names, places & terms, as well as a flow chart of the lineage of French Kings (which can otherwise be confusing)

- The Life of Joan of Arc by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel (with Joan of Arc series from National Gallery of Art)

- List of all Saint Joan of Arc category pages

Go here for Notes on page readability and navigation.

Notes on sources and quotations:

- I am using the 1902 translation of the Trials by T. Douglas Murray; it has gaps, but can be trusted; most importantly scans of it are readily accessible on Archive.org and GoogleBooks.

- Indented text are direct quotations, so quotation marks are only used for nested (innrer) quotations

- Emphasis added to quotations is mine and not from the sources.

- I have deleted spaces between certain punctuation marks

- I have not otherwise modernized spelling or usage in quotations

Notes on names and spelling:

- I am using the French spelling for proper nouns, except as found in sources, such as Murray's which uses the English "Rheims" over the French Reims.

- Where a name includes a de I will generally but not always use the English "of the", and where it is a d' I will use the original French (saying Duc d'Orléans is far cooler than "Duke of Orleans")

- I'm tempted to use the French Bourguignons and duc de Bourgogne instead of the anglicized Burgundy, but the French nasal consonant "gn" is simply unworkable for the English tongue.

Notes on archaic word use:

Crazy, witch or Saint?

Joan's biographers like to present her with a letter she composed to the King of England,[7] the child-king Henry VI, the day she was given an army to march on the English siege at Orléans.[8] It's a marvelous, crazy letter, almost arrogant at first glance. A second look, though, and the letter yields instead Joan's simplicity and directness. Indeed, she is hardly arrogant: just bluntly honest:[9]

Jhesus † Maria King of England; and you, Duke of Bedford, who call yourself Regent of the Kingdom of France; you, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk[10]; John, Lord Talbot; and you, Thomas, Lord Scales, who call yourselves Lieutenants to the said Duke of Bedford: give satisfaction to the King of Heaven: give up to the Maid,[11] who is sent hither by God, the King of Heaven, the keys of all the good towns in France which you have taken and broken into. She is come here by the order of God to reclaim the Blood Royal. She is quite ready to make peace, if you are willing to give her satisfaction, by giving and paying back to France what you have taken.

It's a useful letter for the biographer, but left unexplained or unattributed to anything but "voices", as they tend rather agnostically to leave it, it makes no sense. Okay, so this illiterate girl from a sidelined village hears "voices" that tell her she will save France and crown its legitimate King. She insists on an introduction to that prince, gets the interview, somehow picking him out of a crowd, undergoes three weeks of questions by all the king's finest minds, and passing the test is given a horse, lance, and suit of armor -- and command of a French army, whereupon she writes a letter to the King of England demanding he surrender all his possessions in and claims upon France -- while displaying knowledge of the English political and military hierarchy... Okay... got it.

Her letter is astonishing. And brilliant.

The English had likely heard the rumors flying about France about "a maid who would save France," but this was their first direct introduction to her. We have no record of how it was received, but it had to be in the back of their minds when she approached Orléans, and on the front of their minds after she routed them, especially this note to the English commander with which she concluded the letter,[12]

You, Duke of Bedford, the Maid prays and enjoins you, that you do not come to grievous hurt. If you will give her satisfactory pledges, you may yet join with her, so that the French may do the fairest deed that has ever yet been done for Christendom. And answer, if you wish to make peace in the City of Orleans; if this be not done, you may be shortly reminded of it, to your very great hurt. Written this Tuesday in Holy Week, March 22nd, 1428.

But it wasn't mere psychological warfare as our secular historians contend: Joan was prophesizing. At her Trial of Condemnation at Rouen under the English, the letter was presented as incriminating evidence of witchcraft.[13]

“Do you know this letter?”

Yes, excepting three words. In place of "give up to the Maid," it should be "give up to the King."[14] The words "Chieftain of war" and "body for body"’ were not in the letter I sent. None of the Lords ever dictated these letters to me; it was I myself alone who dictated them before sending them. Nevertheless, I always shewed them to some of my party.

Then, without any prompting or context, she continued,[13]

"Before seven years are passed, the English will lose a greater wager than they have already done at Orlėans; they will lose everything in France. The English will have in France a greater loss than they have ever had, and that by a great victory which God will send to the French."

"How do you know this?"

"I know it well by revelation, which has been made to me, and that this will happen within seven years; and I am sore vexed that it is deferred so long. I know it by revelation, as clearly as I know that you are before me at this moment."

"When will this happen?"

"I know neither the day nor the hour."

"In what year will it happen?"

"You will not have any more. Nevertheless, I heartily wish it might be before Saint John’s Day."[15]

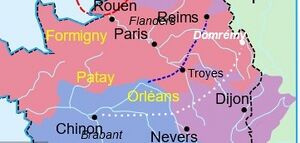

The prediction came on March 1, 1431. Five years later, in April of 1436, Paris was delivered to the French through the Treaty of Arras, which ended the English alliance with the Duke of Burgundy and from which the English would never recover.[16] Skeptical historians will point out the English presence in France continued for another fifteen years, which is true but meaningless, as the English cause was lost with the Burgundian defection.[17] Paris was the endgame, the "greater loss" that Joan had predicted.

In 1449 the French retook Rouen, where Joan was martyred, and in 1453 the English suffered a final defeat at the Battle of Castillon, which ended three hundred years of English control of southwestern France. Those later victories were only possible with the Burgundian realignment at the 1435 Treaty of Arras, which was only made possible by Joan's military and political victories at Orléans and Reims.

Outside of her declarations regarding Orleans and the crowning of the Dauphin, this prophesy is her most significant -- and one that no one would or could have contemplated at the time, when the English were reinvigorated by her capture and had Henry VI crowned at Paris later in the year after her execution.

Upon Joan's capture, the Duke of Burgundy issued a public acclamation of victory, announcing,

‘Very dear and well-beloved, knowing that you desire to have news of us, we[18] signify to you that this day, the 23rd May, towards six o’clock in the afternoon, the adversaries of our Lord the King[19] and of us, who were assembled together in great power, and entrenched in the town of Compiègne, before which we and the men of our army were quartered, have made a sally from the said town in force on the quarters of our advanced guard nearest to them, in the which sally was she whom they call the Maid, with many of their principal captains .... and by the pleasure of our blessed Creator, it had so happened and such grace had been granted to us, that the said Maid had been taken ... The which capture, as we certainly hold, will be great news everywhere; and by it will be recognized the error and foolish belief of all those who have shewn themselves well disposed and favourable to the doings of the said woman. And this thing we write for our news, hoping that in it you will have joy, comfort, and consolation, and will render thanks and praise to our Creator, Who seeth and knoweth all things, and Who by His blessed pleasure will conduct the rest of our enterprizes to the good of our said Lord the King and his kingdom, and to the relief and comfort of his good and loyal subjects.

We see just how important was Joan's capture to the English and Burgundians: if she is not of divine intervention, they reasoned, then her successes were not legitimate, including, by reference to the English King, the coronation Joan engineered of the French King. Royal legitimacy relied on faith in God's plan, so Joan's capture justified the English cause. One of clerics who saw Joan the day "she was delivered up to be burned,"[20] Jean Toutmouille, recalled the moment:[21]

For, before her death, the English proposed to lay siege to Louviers ; soon, however, they changed their purpose, saying they would not besiege the said town until the Maid had been examined. What followed was evident proof of this ; for, immediately after she was burnt, they went to besiege Louviers, considering that during her life they could have neither glory nor success in deeds of war.

In the early stages of Henry V's invasion and rampage across Normandy, 1418, in a particularly violent siege and occupation, the English took the loyal French town of Louviers, killing and ransoming townspeople. In the French revival following Joan's entry, La Hire retook the town in December 1429, which greatly offended the English leadership, and added to their resentment and hatred of Joan. The town remained in French hands through her trial and may well have been the source of growing English impatience with the trial's progress into May of 1431, as the English leadership grew testy over procedures required of an ecclesiastical trial.[22] Around the time of Joan's execution, the English launched the attack, having amassed an unusually large army for the action. Louviers fell, finally, on October 25.[23] Clearly, it was a huge deal for them, and not just because of the town's strategic location south of Rouen and along the south bank of the Seine, and thus along a strategic route to Paris.

In France, meanwhile, Joan's role as emissary of God had been replaced by a mystic, Guillaume of Lorraine, known as "the Shepherd of Gévaudan." Unlike Joan, the Shepherd was actually a shepherd. And, unlike Joan, he demonstrated an outward sign, having the stigmata on his hands, feet and chest. The Bishop of Reims promoted the Shepherd, a most cynical move, as he just wanted to denigrate Joan whom he never liked and whom he distrusted for her insistence upon military conquest of the Burgundians,

Skeptical historians point to the various prophetic figures who appeared around the time of Saint Joan, which, they either state or infer, confers by coincidence of the moment, similar false prophesy upon Joan.[24] One such figure, Catherine de la Rochelle, Joan dismissed as a fraud, having asked her Voices about her,[25]

I spoke of it, either to Saint Catherine or to Saint Margaret, who told me that the mission of this Catherine was mere folly and nothing else.

Joan advised Charles VII not to pay any attention to her. She told the Rouen court,[26]

I told Catherine that she should return to her husband, look after her home, and bring up her children.

Catherine de la Rochelle had joined up with a Franciscan Friar, Brother Richard, a messianic preacher who had been in Paris preaching repentance and divine retribution.[27] In 1429, as news of Joan raced across France, the Burgundians put two and two together and went after him. He fled to Troyes, where he met Joan. The Rouen Trial, with its clerics from Paris, quizzed Joan extensively about her relationship with him. Joan recounts only that he was he was upset at her dismissal of Catherine de la Rochelle and that when he first approached her at Troyes he made a sign of the Cross and threw holy water upon her:[28]

I said to him: "Approach boldly, I shall not fly away!"

Let's just say she wasn't impressed by him. The Rouen court insinuations of a diabolical connection to Brother Richard went nowhere. In France, Brother Richard wore out his welcome, and was relegated to Poitiers, the French bishops telling him to tone it down. Around this time, another mystic, Pierronne, appeared in Brittany, traveling from town to town speaking of saving France and that God, appearing to her in a white robe and a purple tunic, had sent her to affirm and support Joan's mission.[29]. She attracted followers, one of whom was arrested with her outside of Paris by the University clerics who were hectored by Joan's successes. Perrionne remained defiant and refused to recant, and was burned at the stake on September 3, 1430. Her follower recanted and was spared.

Upon Joan's execution, the Charles VII's court turned to the Shepherd of Gévaudan. In June of 1431, amidst the campaign for Louviers, the young man was ridden to battle near Beauvais, where the English destroyed the French contingent, which included La Hire, who escaped.[30] The Shepherd was delivered by the English the ecclesiastical court in Paris, which without much inquiry found him guilty of heresy, including to have had the wounds of the Savior imprinted upon him by the Devil, and had him burned.[31]

While skeptical historians use these mystics to impugn Joan's divine mission, they importantly served to rally the French people around her, before and after her death. That the Shepherd was useless militarily merely reinforced the accomplishments of Joan. Nevertheless, they became useful examples for the English and Burgundians -- and certain historians. We should have no surprise at the appearance of various prophets and mystics upon Joan's entry. She inspired, inflamed, and, with or without the Holy Spirit, created a deeply spiritual moment for France.

With Louviers taken, and the path to Paris fully clear, in December of that year, Henry VI was coronated at Paris in an elaborate ceremony as Henry II, King of France. It was not just English assertion of the Treaty of Troyes, in which Charles VI yielded the French throne to the English upon his death, it was the English declaration of victory over the Maid. Along with the capture of La Hire in May, 1431, the demise of Joan was looking fruitful for the English. British historian Barker notes,[32]

The execution of the Pucelle seems to have changed the fortunes of the English, for Xaintrailles was not the only feared Armagnac captain to lose his liberty this summer. In the very week that Jehanne was burned, ‘the worst, cruellest, most pitiless’ of them all, La Hire, was captured and committed to the castle of Dourdon, close to La-Charité-sur-Loire. A few weeks later, on 2 July, the sire de Barbazan, whom La Hire had rescued from his long incarceration at Château Gaillard the previous year, was killed in a battle against Burgundian forces at Bulgnéville, twenty miles south-west of the Pucelle’s home village of Domrémy. René d’Anjou, Charles VII’s brother-in-law and confidant, was taken prisoner in the same battle, temporarily ending his struggle to assert himself as duke of Bar by right of his wife.

The French, too, yielded to the theory that her capture marked change of fortune. France fell to episodic cat-and-mouse play, both militarily[33] and diplomatically,[34] hoping to weaken the English while luring the Burgundians to their side. By the time of Joan's death, it had yielded no results, yet following her death the strategy continued, with French military actions focused on consolidation and not advance, on defense not attack.[35]

Still, Joan's prophesy unfolded.

As the English-Burgundian alliance unwound, the English King returned home, the English leadership lost confidence, and the French warriors who were the most loyal to Joan started taking more and more land, especially around Paris. In 1435, with the death of the English Duke of Bedford, the Burgundians abandoned the alliance and signed the Treaty of Arras with the French. Soon after, the citizens of Paris opened the city gates to the Bastard of Orlėans and the French army. While it took another twenty years for the end of the Hundred Years War, the outcome by then was sealed, and Charles VII was able to not just consolidate his realm, but reorganize it politically and militarily, significantly contributing to the creation of the modern state in France.

Having liberated Orlėans in 1429 and leading the French army across France to clear the way for the Dauphin's coronation at Reims, to both sides Joan was either a witch or a prophet -- possessed by fiends, or of God. However, detraction is easier to sustain than faith, so the English held to their hatred of Joan longer than did the French their confidence in her. Following the coronation of Charles VII, with Joan at the height of her popularity, the Chancellor, whose goal was ever reconciliation with the Burgundian faction, not its defeat, worked to undermine her. For him, the Maid had at best served to put the issue on the table, but most inconvenient was all this insistence on taking Paris, which was a Burgundian property.[36] As Joan testified at the Rouen trial when questioned about the mystic, Catherine de la Rochelle, whom Joan dismissed,[37]

She told me she wished to visit the Duke of Burgundy in order to make peace. I told her it seemed to me that peace would be found only at the end of the lance.

The Chancellor did not want an attack upon Paris, which is why immediately after the coronation of Charles VII, which he administered as Archbishop of Reims, he went to Saint Denis to negotiate a truce with the English to work around all this trouble Joan had caused. Thus, upon her capture by the Burgundians in May of 1430, de Chartres was downright enthusiastic, announcing publicly to his diocese:

God had suffered that Joan the Maid be taken because she had puffed herself up with pride and because of the rich garments which she had taken it upon herself to wear, and because she had not done what God had commanded her, but had done her own will.[38]

Gerson had died by then, so we can't know his reaction. But Gélu's diocese issued prayers for her release, which were repeated across France, including,[39]

that the Maid kept in the prisons of the enemies may be freed without evil, and that she may complete entirely the work that You have entrusted to her.

Nevertheless, it was de Chartres who controlled French policy, and despite regular Burgundian duplicity he kept trying to negotiate a settlement. After Joan's capture, only minor battles and outright defeats followed, so Joan's legitimacy further faded -- as did de Chartre's need to put up with her.

Historians have attributed Charles' treatment of Joan after his coronation to cynicism and opportunism. I'm not convinced, as he was subject to the machine as much as he was its head. He ended up playing both sides, letting Joan go forth against the English and Burgundians while withholding the resources she needed to prosecute the program. Joan's capture, which was a direct consequence of the French transition from Joan's aggression to the Chancellor's diplomacy, became the excuse to abandon her program altogether upon her capture.

For their part, the English and Burgundians knew full well what this young woman had done, and the danger she posed, even from prison.[40] Although after her capture Joan was no longer a military threat, the coronation of Charles VII was a deep wound that could be healed only by delegitimizing the event by delegitimizing its author, Joan. The Burgundian clerics centered mostly at Paris faced the same problem, and so were most happy to serve as the instrument of recovery for the English. By ingratiating themselves to the English with the needed ecclesiastic stamp of heresy upon Joan, the clerics at the University aimed to elevate themselves and the French Assembly to the level of the English Parliament.[41] Modern historians emphasize these political machinations[42] as the primary motive for Joan's Trial at Rouen.

One may wonder, though, that it is not possible to maintain at once personal ambition and sincere belief, especially when the two affirm one another. Thus did de Chartres justify undermining Joan; thus did the Paris clergy justify her trial; thus did the English desperately need her denunciation; thus did the English Earl of Warwick demand that, when Joan fell dangerously sick in prison, he ordered the doctors to do whatever they could to sustain her:[43]

as the King would not for anything in the world, that she should die a natural death; she had cost too dear for that; he had bought her dear, and he did not wish her to die except by justice and the fire.”

And thus did the English Duke of Bedford, several years later, yet blame his troubles in France on Joan, writing to his King,

a greet strook upon your peuple that was assembled there [at Orleans] in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadded believe, and of unlevefull doubte that thei hadded of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fals enchauntements and sorcerie. The which strooke and discomfiture nought oonly lessed in grete partie the mobre of youre people.[44]

Historians have suggested that Bedford was merely casting blame upon "the Pucelle" to excuse his own poor performance.[45] Indeed, he submitted a "written statement he had before given to the King in defense of his conduct in the government of France", explaining:[46]

he then recapitulates the services which he had rendered at the commencement of the wars in that kingdom after the death of King Henry the Fifth up to the time of the siege of Orleans ... and ascribes his subsequent want of success to a lack of sad belief and of unlawful doubt that the people had of a disciple and limb of the fiend called ‘the Pucelle’- that used false enchantments and sorcery; he reminds the King that he had himself come to England to explain the state of affairs in France, and used his utmost endeavours, but without success, to procure the means to carry on the war; he expresses his deep regret that that country should be lost after the great expenditure of blood and treasure which had occurred ; he advises that the revenues of the duchy of Lancaster, which had been vested in Cardinal Beaufort and others for the purpose of fulfilling the will of the late King, should be wholly employed in the defence of France...

He wasn't rationalizing that he had lost to a witch -- this he admits: he was asking for more money to make up for it. Bedford fully believed that Joan, who his government executed four years before, was a "fiend". Near the end of the Trial at Rouen, after reading to Joan the "Twelve Articles of Accusation" (consolidated from seventy), a priest and "celebrated Doctor in Theology,"[47] Pierre Maurice, who was deeply tied to the English, lectured Joan on the "peril" she was subjecting upon her soul:

Do not allow yourself to be separated from Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who hath created you to be a sharer in His glory ; do not choose the way of eternal damnation with the enemies of God, who daily set their wits to work to find means to trouble mankind, transforming themselves often, to this end, into the likeness of Our Lord, of Angels and of Saints, as is seen but too often in the lives of the Fathers and in the Scriptures. Therefore, if such things have appeared to you, do not believe them. The belief which you may have had in such illusions, put it away from you.

At this point in the Trial, they just wanted to do away with her, which is why they forced her into the confession and subsequent relapse upon putting back on the men's clothing. Upon that discover, the Bishop of Beauvais exclaimed to the English lord, Warwick,[48]

She is caught this time!

The Bishop, Cauchon, was entirely compromised to the English by his ambitions, but he was convinced that Joan was of the Evil One. He probably never imagined how long the trial would go, as his frustration grew with every unexpected response and retort from Joan to the best theological traps the University of Paris' finest minds could throw at her. One of the priests there who testified at the Trial of Rehabilitation recalled that her responses were inspired:[49]

When she spoke of the kingdom and the war, I thought she was moved by the Holy Spirit; but when she spoke of herself she feigned many things: nevertheless, I think she should not have been condemned as a heretic.

It's an interesting testimony coming amidst a politically-charged reassessment of a trial he had participated in twenty-four years before on behalf of the enemy, so his hedge that "when she spoke of herself" is interesting. His mixed statement shows either that he was putting her in as good a light as possible -- as regarded the King of France, who was under a reassessment as much as was Joan: justifying Joan meant justification for him. Nevertheless, de la Pierre was under oath, and we must take his testimony as such: his only explanation was that Joan had to have been inspired by the Holy Spirit.

The Rouen court had its way, and was unequivocal in its condemnation of Joan not just as a heretic, but as a witch, an "invoker of devils." It wasn't about her man's dress[50], and it wasn't about apostasy. It was all about her refusal to deny her Voices. To read the epithet placed upon a placard by the stake on which she was burned is to understand just how real her voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[51]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to the Crucifixion of the Lord himself here and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no, it wasn't. They meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from the trial,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[52]

Those recollections from twenty years later are at odds with testimony taken shortly after Joan's death. Bishop Cauchon ordered a set of testimonies from priests involved in the Trial to show that Joan had fully recanted and admitted she had made the whole thing up:

On Thursday, June 7th, 1431, we the said judges received ex oficto information upon certain words spoken by the late Jeanne before many truftworthy persons, whilst she was in prison and before she was brought to judgment.

The abjuration was useful, but her "relapse" negated it, so Cauchon needed something else, especially after her death, to justify not only her execution but the entire trial, as the English were furious about the relapse. The notary, Manchon recalled,[53]

On Trinity Sunday, I and the other notaries were commanded by the Bishop and Lord Warwick to come to the Castle, because it was said that Jeanne had relapsed and had resumed her man's dress.

When we reached the Court, the English, who were there to the number of about fifty, assaulted us, calling us traitors, and saying that we had mismanaged the Trial. We escaped their hands with great difficulty and fear. I believe they were angry that, at the first preaching and sentence, she had not been burnt

What she had said in the abjuration she said she had not understood, and that what she had done was from fear of the fire, seeing the executioner ready with his cart.

Known as the "Subsequent Examinations," the testimony came from several of the most extreme accusers against Joan, including a Canon of Rouen, Nicolas Loyseleur, who visited Joan in her prison cell, pretending to be from Lorraine to gain her confidence and confession, all of which he reported back to Cauchon. It's an interesting document, as it shows what Cauchon still needed to prove, and had failed to achieve in the Trial. Two points were addressed by those deposed, one, that Joan admitted her "Voices" had deceived her, and the second, of great importance to Cauchon, that the sign Joan had given privately to Charles VII was not a real crown delivered by an angel. Leaving it that an angel had crowned Charles VII was, shall we say, disadvantageous to the English cause, demonstrating the fragility of, or Burgundian sensitivity to, the English claim in the French throne. Early in the trial, on March 10, Joan was asked,[54]

What was the sign you gave your King?

Her answer infuriated them:

Will you be satisfied thaf I should perjure myself? "

"Have you promised and sworn to Saint Catherine that you will not tell this sign?"

The reference to Saint Catherine was a jab that Joan ignored:

I promised and swore not to tell this sign, and for my own sake, because I was pressed too much to tell it, and then I said to myself: "I promise not to speak of it to anyone in the world." The sign was that an Angel assured my King, in bringing him the crown, that he should have the whole realm of France, by the means of God's help and my labours; that he was to start me on the work — that is to say, to give me men-at-arms; and that otherwise he would not be so soon crowned and consecrated.

They were confounded:

"How did the Angel carry the crown? and did he place it himself on your King s head?" "The crown was given to an Archbishop — that is, to the Archbishop of Rheims — so it seems to me, in the presence of my King. The Archbishop received it, and gave it to the King. I was myself present. The crown was afterwards put among my King's treasures."

The questioning turned to the details, which Joan dangled before them,[55]

"It is well to know it was of fine gold; it was so rich that I do not know how to count its riches or to appreciate its beauty. The crown signified that my King should possess the Kingdom of France."

"Were there stones in it?"

"I have told you what I know about it."

On May 2 at the "Public Admonition by the Judges" in which the Twelve Charges were read in public, the court demanded, again, clarification about the "sign" about the crowning of Charles[56]

On the subject of the sign given to your King... to whom or to some of whom you say that you shewed the crown, these being present when the Angel brought it to the King, who afterwards gave it to the Archbishop?

And again, on May 9, the day the court considered submitting her to torture,

"On the subject of the crown which you say was given to the Archbishop of Rheims, will you defer to him?"

"Make him come here, and I will hear him speak, and then I will answer you. Nevertheless, he dare not say the contrary to what I have said thereon."

The transcript continues,

Seeing the hardness of her heart, and her manner of replying. We, the Judges, fearing that the punishment of the torture would profit her little, decided that it was expedient to delay it, at least for the present, and until We have had thereupon more complete advice.

So much emphasis was put on her clothing that this infuriating matter went unanswered, and so needed clarification even after her death. In his testimony, Loyseleur knew what was needed:[57]

Wednesday, the Vigil of the Feast of Corpus Christi, I repaired in the morning with the venerable Maître Pierre Maurice, to the place where Jeanne, commonly called the Maid, was detained, to exhort and admonish her on the subject of the salvation of her soul. She was besought to speak truth on the subject of that Angel who, she had declared, had brought to him she called her King a crown, very precious, and of the purest gold : she was pledged not to hide the truth, inasmuch as nothing more remained to her but to think of her own salvation. Then I heard her declare that it was she herself who had brought him she called her King the crown in question ; that it was she who was the Angel of whom she had spoken ; and that there had been no other Angel but herself Asked if she had really sent a crown to him whom she called her King, she replied that he had no other crown but the promise of his coronation — a promise she had made in giving to her King the assurance that he would be crowned.

Then he hit upon the next matter of importance,

In the presence of Maître Pierre Maurice, of the two Dominicans, of you, the Bishop, and of several others, I heard her many times declare that she had really had revelations and apparitions of spirits; that these revelations had deceived her; that she recognized it in this, that they had promised her deliverance, and that she now saw the contrary; that she was willing to refer to the Clergy to know if these spirits were good or evil; that she did not put, and would no more put, faith in them.

Ending his testimony with,[58]

I exhorted her, to destroy the error that she had sown among the people, to declare publicly that she had herself been deceived, and that through her fault she had deceived the people by putting faith in these revelations and in counselling the people to believe in them; and I told her it was necessary that she should humbly ask pardon. She told me she would do it willingly, but that she did not think she would be able to remember, when the proper moment came — that is to say, when she found herself in the presence of the people; she prayed her Confessor to remind her of this point and of all else which might tend to her salvation. From all this, and from many other indications, I conclude that Jeanne was then of sound mind. She shewed great penitence and great contrition for her crimes. I heard her, in the prison, in presence of a great number of witnesses, and subsequently after sentence, ask, with much contrition of heart, pardon of the English and Burgundians for having caused to be slain, beaten, and damned, a great number of them, as she recognized.

If we to take the words as they are as sworn testimony, and assume their veracity, we can still see several places where the cleric parses out what Joan did not say. He admits a conditionality of Joan's statement, that "she would do it willingly... when the proper moment came", meaning that she had not actually done so. Then, when he says, "From all this, and from many other indications..." the preposition makes no sense if it only modifies that "Jeanne was them of sound mind." Rather, it necessarily continues its conditionality to "She shewed great penitence and great contrition for her crimes," i.e., "From all this, and from many other indications" wasn't just that Joan was "of sound mind" but that her "great contrition" also so came. The claim, then, is derived from more than what he said she said, making it thereby suspect.

Nor was it supported by the witness of others from the same document. The Archdeacon of Eu, Nicolas de Venderès stated that,[59]

Wednesday, 30th day of May, Eve of the Feast of Corpus Christi, Jeanne, being still in the prison of the Castle of Rouen where she was detained, did say that considering the Voices which came to her had promised she should be delivered from prison, and that she now saw the contrary, she realized and knew she had been, and still was, deceived by them. Jeanne did, besides, say and confess that she had seen with her own eyes and heard with her own ears the apparitions and Voices mentioned in the Case.

which qualifies Joan's admission of a deception by her voices to that she "be delivered from prison." The various testimonies follow the same lines of Joan admitting that her voices deceived her and that she lied about the "crown" that the angels had bestowed upon the king of France.

We must note that none of these testimonies suggest that Joan ever denied the existence of the voices -- that would negate the entire point of the trial that she was heretical for having followed false voices, not just lying about them altogether. Furthermore, the supposed admission that the "angel" was, in fact, her, is neither inconsistent with anything she had said before in the Trial nor with the very notion of a divine delivery, at her hands, of the crown to the Dauphin. Whether literal or allegorical, the outcome was the same: Charles VII was crowned at Reims, led there by Joan.

Had Joan actually so repented it would not necessarily negate her "Relapse", although it should have. That it was not invoked prior to her death or offered in her defense at the stake, renders these statements not only irrelevant but overall false.

Nevertheless, Cauchon's final inquiries served their purpose, and soon after the English went on the offensive, thinking themselves cleared of the witch. Later that year, the year of Joan's death, Henry VI was crowned at Paris.

Alas, for the English, the run would not last long. Joan's faithful lietenants, the Bastard of Orleans and La Hire, would not give up, and through a series of small but stinging bites upon the English supply lines to Paris and across Normandy, they weakened the English hold, leading to the Burgundian betrayal. Just as Joan had told the Count of Ligny back in May, 1431 at the castle at Rouen where she was held,[60]

I know that these English will put me to death, because they think, after my death, to win the Kingdom of France. But were they a hundred thousand godons[61] more than they are now, they will not have the Kingdom.

At these words, one of the Count's English escorts, the Earl of Stafford, drew his dagger but was restrained by his compatriot, the Earl of Warwick.

The historical problem of (Saint) Joan of Arc

The most prominent modern biographer of Saint Joan of Arc, Régine Pernoud (1909-1998), a medieval scholar, counsels,[62]

Among the events which [the historian] expounds are some for which no rational explanation is forthcoming, and the conscientious historian stops short at that point.

It's a large concession, that, that some events from the life of Saint Joan of Arc have "no rational explanation," but, apparently, this "conscientious historian" must contain herself to "the facts" and stick to sorting them out for description while avoiding explanation, much less inference from those facts. It's historiographically unenlightening and theologically cowardly -- which is the point, to deny God's hand in the story of (Saint) Joan of Arc.

For Joan, it seems, so it is. As Pernoud admits, if back-handedly, because Joan's motives, actions, and outcomes are so improbable, to attribute them to anything other than divine guidance makes no sense. But since divine guidance is "ahistorical," or merely an article of faith, Joan's motives don't matter historically. Pernoud thereby dismisses them altogether, falling back upon,[63]

The believer can no doubt be satisfied with Joan’s explanation; the unbeliever cannot.

What, then, does the "unbeliever" do with the evidence? That the "unbeliever cannot" accept Joan's own explanations is an easy out from what is plain to see. But the problem is larger. If Joan's Voices were not real, then how to explain their effects?

Such is a core Catholic tenant, drawn from the Gospel of Matthew 7:15-20, from verses labeled in most Bibles, "False Prophets",

Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but underneath are ravenous wolves. By their fruits you will know them.

Just so, every good tree bears good fruit, and a rotten tree bears bad fruit.

A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a rotten tree bear good fruit.[64]

Every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire.

So by their fruits you will know them.

and Matthew 12:33, in which Jesus declares to the Pharisees,

Either declare the tree good and its fruit is good, or declare the tree rotten and its fruit is rotten, for a tree is known by its fruit.

and which the Church at Poitiers on the first examination of Joan on behalf of the French King, employed explicitly when discerning Joan, following 1 John 4:1[65],

Beloved, do not trust every spirit but test the spirits to see whether they belong to God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world.

The "unbeliever" historian has two outs here: the first is to deny the source of Joan's Voices while admitting their effects; the second is to deny their effects, thus denying both.

To the first strategy, historians like Pernoud step around the problem by ignoring the Voices or even their reality, but taking their effects at face value.[66] Others follow the second approach and minimize Joan's historical role altogether, i.e. lesser effects.[67] Or they use both.

So we hear that it was schizophrenia or moldy bread, which at least recognize that Joan heard voices.[68] Others who question the reality of the Voices must fall back on pseudo-psychological conjecture and sociological babble. For example, historian Ann Lelwyn Barstow argues that subjects of Joan's visions were those Saints with which she most closely identified and was most familiar:[69]

One gets the picture of a lively Christianity informing the mind of the young Joan through legends. well-known across Europe ... That she was visited instead [of the Virgin Mary] by Michael, Catherine and Margaret attest to the potency of their legends in Lorraine, to their particular usefulness to a young patriot in time of national distress, and their appropriateness for an independent-minded woman.

Not there weren't any churches in France called "Notre Dame," but, sure, the Church in Domrémy held (and apparently still holds[70]) a statue of Saint Margaret; Saint Catherine was the patron of nearby church; Saint Michael was venerated in Lorraine and was considered the defender of France; so there you have it.

Given that reasoning, one may suppose that some other "local" Saint, say, Saint Drogo, might have equally conveyed God's message to a thirteen year old in rural eastern France, as, while notoriously butt-ugly, he was from the northeast of the country and spoke French. It's nonsense. Of course God sent the Saints that Joan already knew and trusted. To paraphrase Joan, “Do you think God has not wherewithal to select the right Saints for Joan?"[71]

Indeed, remove Joan of Arc from the moment, and things simply did not happen the way they did. That is, she was an unusually significant historical actor, who cannot be simply discarded with, "well, she believed it, that's all that matters." And remove the divine origin of her Voices and she simply did not, was not able to, do what she did.

If Joan's visions were real, then we have perfectly explainable historical causation, including crucial moments of uncertainty or disobedience to her Voices, such as her flustered recantation, called her "abjuration," when threatened in public humiliation before the stake. Skeptical historians point to this moment as evidence that Joan had just made it all up, ignoring that only two weeks before this demeaning public ceremony, when threated with torture she had told the trial judges,[72]

Truly if you were to tear me limb from limb, and separate soul and body, I will tell you nothing more; and, if I were to say anything else, I should always afterwards declare that you made me say it by force.

But so goes the theory that, fatigued and confused, Joan gave the hostile and abusive English-backed court what it wanted and made up stories of the Saints, whom, it (incorrectly) holds, she had not before mentioned.[73] This ignores the fact that several days later, following the instructions of her Voices, Joan recanted her abjuration, stating,[74]

They said to me: "God had sent me word by St. Catherine and St. Margaret of the great pity it is, this treason to which I have consented, to abjure and recant in order to save my life! I have damned myself to save my life!"

Had she really made it up just to please the court, the recanted her recantation knowing she would burn for it? Or do not even cynics have limits? The notary scribbled in the margin of the court register his agreement with the Saints, [75]

Responsio mortifera

People do not die for a lie. Instead, she was lucid, calm, and firm,[76]

"Do you believe that your Voices are Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret?"

"Yes, I believe it, and that they come from God."

If, as, such theories hold, supporters and detractors of Joan were just using her for their convenience, and that the historical record itself reflects that self-interest and not the truth about Joan, why would Joan have said this? They didn't need anything else to to put her to death, so this report actually serves against the interest of the Rouen court, which would now fully act as instruments of a martyrdom, duly recorded in Latin and preserved for us in history.

Medieval historian Juliet Barker sees Joan's career as entirely political in terms of her own ambitions and those of political actors around her.[77] As such, Barker credits the pro-French Armagnacs for using her to push their war against the English-allied Burgundians, even so as to credit the Armagnacs for having engineered not just Joan's introduction to the French prince, Charles the Dauphin, but to her ability to identify him hidden amidst the courtiers -- they tipped her off![45]

Of course there is no evidence for such trickery, but the theory does legitimately point to the Dauphin's equivocal position between the anti-Burgundian and reconciliation factions around him. The problem is that is treats the Dauphin as merely going along for a ride with the Maid just to see what might happen.[78] Hardly. He deliberated, spoke with everyone he could and sent her for an inquiry by the finest clerical minds, "the Doctors",[79]theologians, at Poitiers, to where the several of the leading French clerics were exiled from the English-Burgundian occupation of Paris. The clerics investigated her for several weeks, and concluded firmly that the King must not deny God and so must send her to Orleans at the head of his army. Historians have argued that the investigation at Poitiers was just for show, or that the good Doctors merely reviewed her, shrugged their shoulders, saying, "let's see what happens."

Rather, they advised the King to send her with the Army, "placing hope in God" -- meaning to trust that God is in her.[80] Our secular historians seemingly have no idea what "Christian hope" is, and so they see the Poitiers recommendation as expedience, ambivalence, or deflection. They entirely misunderstand the word, "hope".

Per the Catechism of the Catholic Church,[81]

Hope is the theological virtue by which we desire the kingdom of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ's promises and relying not on our own strength, but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit.

Accordingly, the Poitiers Doctors concluded the recommendation to send her to Orleans with,

The king, given the investigation conducted of the said made, as far as he is able, and that no evil is found in her, and considering her reply, which is to give a divine sign at Orléans; seeing her constancy and perseverance in her purpose, and her insistent request to go to Orléans to show there the sign of divine aid, must not prevent her from going to Orléans with her men at arms, but must have her led there in good faith, placing hope in God. For doubting her or dismissing her without appearance of evil, would be to repel the Holy Spirit, and render one unworthy of the aid of God, as Gamaliel stated in a council of Jews regarding the apostles.

No illusions about it. And not just about some cross-dressing prophet. As the most significant of these advisors, Bishop Jean Gerson, observed, allowing a girl to lead an army isn't a trial balloon. In his apologia for Joan written shortly after her victory at Orléans, he observed that to give an army to a woman isn't just crazy, it's dangerous:

The king's council and the men-at-arms were led to believe the word of this Maid and to obey her in such a way that, under her command and with one heart, they exposed themselves with her to the dangers of war, trampling under foot all fear of dishonor. What a shame, indeed, if, fighting under the leadership of a woman, they had been defeated by enemies so audacious! What derision on the part of all those who would have heard of such an event![82]

The historians reply that this was after-the-fact rationalization, and, besides, the Dauphin was obsessed with prophesy, so he naturally fell to the latest seer.[83] Or, as does Barker, the Dauphin's military situation was not as dire as Joan's "cheerleaders"[84] have claimed, so, by implication, she wasn't the essential actor in the moment and there was no risk in sending her. But not even Barker claims that without Joan's involvement the French would have won at Orléans. The theory is ever insufficient to explain the events. Worse Barker is simply arguing against the historical record. The Dauphin's ecclesiastical advisers whom he asked to investigate her before his endorsement of her, made it very clear as to why they recommended nothing against the girl:[85]

The King, given his necessity and that of his kingdom

Unlike historians, the actors of Joan's day had to to decide: either Joan acted on voices of God -- or of Satan. There was no in between. Just ask the English and Burgundians who knew full well what this young woman had done and why.[40] The rage of the Rouen ecclesiastical Court and its English backers that condemned her is in inverse proportion to Joan's faith in her Visions and the reality her people of France understood them to be. To read the epithet the English placed upon a placard by the stake is to understand just how real her Voices were:

Joan, self-styled the Maid, liar, pernicious, abuser of the people, soothsayer, superstitious, blasphemer of God; presumptuous, misbeliever in the faith of Jesus-Christ, boaster, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.[51]

It ought not take much faith to see straight through to a typology of the crucifixion of the Lord himself and the fury of his executioners, which stand for us in the Gospels as more evidence of the Lord's divinity. Uninformed by faith, the condemnation of Joan is just hyperbolic political statement. Oh no -- they meant it, and meant it hard. Listen to the priest Jean Massieu, Joan's escort to and from her prison cell at the Trial of Condemnation, including to lead her to the stake,

I heard it said by Jean Fleury, clerk and writer to the sheriff, that the executioner had reported to him that once the body was burned by the fire and reduced to ashes, her heart remained intact and full of blood, and he told him to gather up the ashes and all that remained of her and to throw them into the Seine, which he did.

Or Isambart de la Pierre, a Dominican priest who witnessed the Trial,

Immediately after the execution, the executioner came to me and my companion Martin Ladvenu, struck and moved to a marvellous repentance and terrible contrition, all in despair, fearing never to obtain pardon and indulgence from God for what he had done to that saintly woman; and said and affirmed this executioner that despite the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal which he had applied against Joan’s entrails and heart, nevertheless he had not by any means been able to consume nor reduce to ashes the entrails nor the heart, at which was he as greatly astonished as by a manifest miracle.[52]

All our skeptics can do is to question the motives of these testimonies, saying that de la Pierre and Ladvenu were covering up their own shameful involvement in the Condemnation Trial at Rouen. Perhaps, but even if true, the testimony affirms Joan's innocence. The details, though, are hard to ignore: "her heart remained intact", "the oil, the sulphur and the charcoal" -- memory works this way, not imagination.

These historians engage in the same process as writing a book on the life of Jesus as a non-believer.[86] You'd get caught up in denying the Lord's virgin birth, denying the miracles, denying the resurrection, and, ultimately, as some do, denying his historical presence altogether -- understandably so, as the story of Christ makes no sense without his divinity.[87] Actually, Thomas Jefferson did just this, conducting a now obscure and theologically meaningless cut and paste job on the New Testament, from which he extracted the angels, prophesies, miracles, and the Resurrection.[88] Accepting the historicity of Christ without the miraculous requires denying the authenticity of the Gospels and attributing them to post hoc contrivances.[89] It gets messy and, frankly, serves merely to deny Christ rather than understand him.

And with Saint Joan that's where our historians land. Pernoud denies that Joan was, in CS Lewis' terms[90], a madman, but neither was she divinely guided. So all we have left is that she was a liar -- and thus of the devil, something Pernoud, a deep admirer of Joan, never broaches, although the English put her to death for it.

CS Lewis prefaces his argument about Christ's divinity by noting,

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say.

The logic applied to Joan goes the same way: treating her merely as an historical character debases what she was and did. So it is that Pernoud concludes that when "confronted by Joan" all we can do is to "admire" her, as the common people have since the 15th century, for "in admiring [they] have understood her":

They canonised Joan and made her their heroine, while Church and State were taking five hundred years to reach the same conclusion.[91]

That's as close as Pernoud will come to an historical "saint" Joan -- that she was "canonized" in the hearts of her countrymen.

While affirming Joan's popular canonization, Pernoud incorrectly claims that the "Church and State" didn't understand her until 1921, forgetting that Joan's "Rehabilitation Trial" and its declaration of her innocence was, in Pernoud's own words, "in the name of the Holy See."[92] This historian ought to know that very few of the laity were canonized before the 20th century, including the 16th century Sir Thomas More, who wasn't canonized until 1935, and despite great hostility for it from the Anglican Church. Saint Joan's canonization underwent a similar dynamic, delayed not just by English objections but by the intervention of the French Revolution and overall 18th and 19th century European anti-clericalism and anti-monarchism.

Free of having to address whether Joan's spiritual events were real or not, the secular historiography leads to sentimentalized and historically insufficient views of Joan's contemporaries and her legacy. So we get these dull statements of Joan's legacy, such as at end of one Pernoud's books,

It remains true that, for us, Joan is above all the saint[93] of reconciliation—the one whom, whatever be our personal convictions, we admire and love because, over-riding all partisan points of view, each one of us can find in himself a reason to love her.[94]

That's no better than this, from the collective wisdom of contributors to the "Joan of Arc" entry at Wikipedia, casting Saint Joan to the eye of the beholder:[95]

Joan's image has been used by the entire spectrum of French politics, and she is an important reference in political dialogue about French identity and unity.

But what is equally bewildering is that these historians mostly ignore the most thorough, considered, and balanced investigation into Joan, that conducted by the Vatican itself. On consideration of a person for beatification and canonization, the Church investigates the case, and thoroughly, assigning advocates for and against the candidate.[96] There were serious charges against Joan, including to have waged war on a Holy Day, disobedience to her Voices, questions about her purity, and her "unsaintly" reluctance to be burned to death (i.e. martyrdom). The Church duly considered those objections, and on May 16, 1920, canonized Saint Joan of Arc.

A final problem the story of Saint Joan presents to secular historians concerns the extensive historical record which they use to argue against her sanctity. That record consists primarily of the transcripts of Joan's two "trials", the "Trial of Condemnation" at Rouen under the English-backed court, and the "Trial of Rehabilitation", over two decades after her death, under the authority of the French government. Regarding the first, doubting historians seek inconsistencies in Joan's testimony and attribute to her claims about her Voices either deceit or emotional frailty under the duress of the trial. These historians then pick and choose what they want to believe from Joan's testimony or from that of the trial court. As to the Rehabilitation Trial, they dismiss it altogether or in part as a propaganda exercise to reverse engineer Charles VII's legitimacy through Joan's exaggerations and outright lies about her saintliness and accomplishments. There exist a rather large body of additional contemporaneous documents, including letters, including some that Joan herself dictated, receipts, "chronicles", which are ongoing observations about past and current events that cover Joan's affairs in real time, as well as official reports on her, such as a summary endorsement of her from the Dauphin's clerics who interviewed her extensively prior to Orléans. Finally there are literary and theological works written shortly after Orléans, and then over the next decades but within the lives of those who witnessed her.

Here's the problem: without that extensive record, Joan's accomplishments yet stand. Rather than building a hagiographic recreation of her life that is passed on orally through the centuries, and written down much later, as we have it for the early Saints, we have an enormous amount of detail to inform of her life. There is no argument as to the proximity of the record to the events, which is historical gold. While it is a legitimate historical exercise to analyze and interpret that record, we can with certainty say that if Joan of Arc did not claim divine guidance, yet accomplished what she did, she would be universally hailed historical hero who, for example, as a young village girl inexplicably knew how to wield a lance, charge a fortification, or, unbelievable as it would sound, talk her way into the French court and personally meet the King. It is her claims of divine guidance that make it all so doubtful to these historians, not her acts themselves.

My concern here is that a historical treatment of Joan that frees itself of having to address whether her spiritual events were real or not, or that attempt to demystify them, leads to significant misreading of the facts. We cannot comprehend the motives and choices of Joan herself, much less those of her followers and detractors without it. We cannot understand Joan of Arc except as a Saint. And when we do, her story -- her historical record -- makes perfect sense.

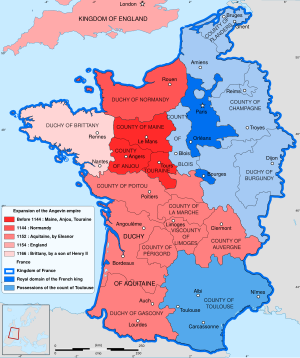

The mess only a Saint could fix

Joan was likely born in January of 1412 in a village in eastern France that lay on the margin of warring French factions and the quasi-independent Duchy of Lorraine. She was about eight years old when in 1420 the French King Charles VI, "the Mad", through marriage to his daughter, granted to Henry V of England succession to the French crown. As did his recent predecessors, when Henry ascended to the English throne in 1413 he proclaimed himself King of France as well. Unlike those predecessors, however, he asserted the English claims on France, including its former possessions in Normandy and southwestern France. Disunited,[97] the French failed to address Henry's demands cohesively, or they simply did not take him seriously.[98]

Rejecting the French response, which was essentially, "here, take another princess,"[99] in 1415 Henry invaded Normandy, reviving the ongoing but episodic French succession conflict we now call the "Hundred Years War". At the famed Battle of Agincourt, Henry destroyed French forces that consisted mostly of loyalists to the House of Orléans, while its French rival, the House of Burgundy, sat out, possibly by agreement with the English.[100] Animosity continued between the French factions, further weakening Charles VI, who had long suffered attacks of severe mental illness which periodically left his rule up for grabs.

Born in 1368, Charles VI assumed the throne as a minor at age eleven, so France was ruled by a regency council made up of his father's brothers, but dominated by the youngest, and most ambitious of them, Philip "the Bold", Duke of Burgundy.[101] At twenty years old, In 1389 Charles VI assumed full control from his uncles, whom he forced out by reinstalling his father's old and loyal advisors. While his mental illness must have been already evident, in 1392 Charles lost control of himself and deliriously attacked his own guard, killing a knight and several others.[102] The Duke of Burgundy stepped in again and took command of the King. However, a new regency council was established under the authority of Charles's Queen, Isabella of Bavaria. Between mental bouts Charles exercised rule in competency, but he largely let his wife represent him to the council while the court tiptoed around him, keeping him amused and distracted. Henceforth, she and the the King's younger brother, Louis II, Duke of Orléans,[103] angled for power over Charles' uncles, especially the Duke of Burgundy.

As regents, the dukes of Orléans and Burgundy largely managed state affairs in conciliation, although when one was traveling the other would pull some stunt back at the court. However, when Philip, the Duke of Burgundy, died in 1404 the Duke of Orleans removed Philip's son, John the Fearless, from both the council and the Royal treasury, a huge powerplay. In 1407, John got back by having Louis assassinated, an act that John not only admitted but acclaimed, justified by removal of excessive taxes Louis had imposed upon Paris and as a general appeal to Parisian autonomy. Additionally, the all-powerful University of Paris was upset that the Duke of Orléans had returned French alliance from the Avignon antipope back to the Roman Pope. Louis had supported the antipope in exchange for an annulment of a prior betrothal of the Princess of Hungry, whom he was angling to marry in order to take the title King of Hungry.[104] After that deal fell through, Louis returned French official allegiance to the Roman Pope, Benedict XIII.

Such is the life of the little brother of a king, only Louis' life was further complicated by a reputation for debauchery[105] and rumors of an affair with his brother's wife, the Queen of France. True or not, the stories came from the camp of Philip of Burgundy, who certainly knew the intimate lives of the court. Since Charles VI son, the Dauphin Charles, was born in 1403, the timeline fits, although there seems not to have been any such rumors about the other children born in the 1390s and early 1400s, including a son born in 1407.[106]

The year after the murder of Louis, a University of Paris theologian, Jean Petit, gave a speech in front of the King justifying the murder of his brother as legitimate tyranicide.[107] Charles VI was powerless to do anything about it, as the Duke of Burgundy held Paris militarily and forced the King to issue an official pardon. The King responded with appointment of an army of 500 that escorted the rival factions for their protection and was pledged to defend whichever side was attacked by the other. One of the most important French theologians, Jean Gerson, was appalled by Jean Petit's speech, and issued a formal objection. A few years later, in 1413, the Duke of Burgundy prompted a street takeover of Paris, called the Cabochien revolt,[108] during which Gerson's house was ransacked and the cleric nearly killed, certainly under orders of the Duke. Gerson fled to the vaults of Notre Dame where he remained hidden for two months. He attributed his escape to the protection of Saint Joseph, whose devotion he henceforth promoted.[109]

The Paris rebellion lasted but four months, and was put down harshly by the new Duke of Orleans, Charles, who led an army that took over the city, while the Duke of Burgundy fled with his Cabochien supporters. From thus grew the so-called Armagnac–Burgundian civil war (Armagnac for loyalists to House of Orleans). Meanwhile, Charles VI's surviving uncle, John, Duke of Berry, was the sole ballast that kept the calm. However, he died in 1416 shortly after the Battle of Agincourt, the English victory that fully split the French factions -- and in which Charles, Duke of Orleans, was captured, leaving a power vacuum on the Armagnac side.

While not officially siding with the English as yet, the Burgundians at the least accommodated their presence in northern France. In 1418 the teenage Dauphin ("prince") Charles, was forced out of Paris by Burgundian elements and fled south to Bourges, where he set up his court. The next year, the Duke of Burgundy, in control of Paris and calling himself Protector of the King of France, approached him to sign a conciliation treaty. So it was agreed to, and to great joy, but the Dauphin's side knew that the Duke was also cutting deals with the English.[110] In 1419 the Dauphin demanded another meeting in person, which was arranged to take place on a bridge -- indicating just how tense the situation had become. Likely planned in advance, as the Dauphin was not present, his escorts axed and killed John the Fearless.

The Burgundians now openly aligned with the English and negotiated the Treaty of Troyes with King Charles VI. Most importantly, Queen Isabeau supported the deal which, through marriage of their daughter to Henry V of England, yielded succession to Henry as King of France, thus cutting off her son, the Dauphin Charles. Among those who negotiated the treaty was a Burgundian Bishop who would later persecute Saint Joan.[112] With the Duke of Orleans in captivity in England, the Dauphin sidelined for the murder of the Duke of Burgundy, and ratified by the Estates-General at Paris, Henry V triumphantly arrived to Parish to sign the treaty.

There's all kinds of messiness here, what with Charles VI bouncing between delusions and paranoias, his wife running the Court during his episodes, and rumored to have had an affair with the King's brother who was murdered by his uncle, whose son, in turn, was murdered by the heir of France, whom the Burgundians claimed was actually the son of the King's brother and so not a legitimate heir. Though weakened, the Armagnac loyalists nevertheless and rather defiantly supported the Dauphin and rallied around his court at Bourges, where, on the death of his father, he assumed for himself the throne of France as Charles VII, although without a full coronation at the traditional city of crowning, Reims, which was controlled by the Anglo-Burgundians. At the same time, Henry V declared himself, according to the Treaty of Troyes, King Henry II of France.

The war escalated from there, with each side taking minor victories as the English secured their hold on northern France and, in 1423 and 1424, inflicted two overwhelming defeats of the French and their Scottish partners.[113] At the prompting of the English, the Burgundians waged slash and burn tactics on areas of French loyalists, including the village of Domrémy, which was subjected to occasional raids and ransoms. By 1428, the French government was going broke and no where, the Duke of Orléans was a still held captive in England, and the French were demoralized and cowered by English armies. Then, in October of that year, the English moved upon the city of Orléans, which was the key to the Dauphin's last line of defense, the Loire River.

A few years before at that village, Domrémy, a thirteen year old girl named Joan began to experience divine voices and visions. The Voices instructed her to lead a good Christian life and, later on, to "go to France" to save save the country and crown its King. In late 1428, Joan's Voices became urgent, telling her "it was necessary for me to come into France" and relieve the city of Orleans from the English siege. [114]That urgency, she told a local French commander in early 1429 was because,[115]

To-day the gentle Dauphin hath had great hurt near the town of Orleans, and yet greater will he have if you do not soon send me to him.

A family affair: Armagnacs v Burgundians

English claims on the throne of France during the 14th and 15th centuries have as bookends several scandals that led to succession crises of the French throne. Just prior to his death in 1314, French King Philip IV's daughter, Isabella of France, who was English King Edward II's wife and thus queen of England, accused the wives of Philip's three sons of adultery. One of those, Margaret of Burgundy, was the Queen to King Louis I of Navarre, who later that year became King Louis X of France.[116] Margaret was jailed for the adultery charges, and so became Queen of France from prison.[117]

In a further complication that reflects upon the story of Saint Joan, Louis X was unable to divorce her, as Pope Clement V died that April and the Papal See remained empty for two years over disputes between the French and Italian Cardinals (see Popes and antipopes flowchart). By the time in 1315 that Margaret either got around to dying of a bad cold from poor conditions in prison, or was helped to not breath any more (cause of death disputed), Louis had only one child, Joan. He quickly remarried and his queen duly got pregnant, but Louis died during her fourth month, apparently after drinking too much chilled wine, or perhaps wine laced with poison. On his deathbed he named Joan his heir, as there was no assurance the baby would be a boy, much less survive infancy.

The French nobility wouldn't have it, and invoked the ancient Salic Law from Clovis that barred women from inheriting the throne. So Joan became Joan II of Navarre but not Queen of France. Meanwhile, Louis' second wife's child was a boy, but he died at four months,[118] leaving Louis' brother, who was regent following Louis' death, to the throne. The brother ruled as Philip V from 1316 to 1322, but his wife, Joan, who was cleared of the charges, issued no male heirs. So the throne passed to the third brother, who became Charles IV, who upon ascension he was granted a divorce from his wife who was in prison under charges of adultery.[119] His new queen died during a premature birth, and all but one daughter of a third wife died young. So upon the death of Charles IV, there was no male heir, either, ending, thus, the House of Capet.

From these events arose the opportunity for Edward III of England, whose mother was the very "She-Wolf of England", Isabella of France, who had launched the series of miseries that followed the charges of adultery of her brothers' wives. With her lover, Roger Mortimer, Isabella usurped her husband Edward II and placed her son on the English throne, making him, as the nephew of Charles IV through his mother, both King of England and the most direct heir to the French crown.[120] But the French nobility again asserted Salic Law and in 1328 gave the throne to Charles' paternal cousin, Philip of Valois, who as Philip VI (1328-1350), started the House of Valois dynasty, to which the Dauphin of Joan's day belonged. Nine years and many disputes later, Edward III declared himself legitimate King of France and invaded the continent.